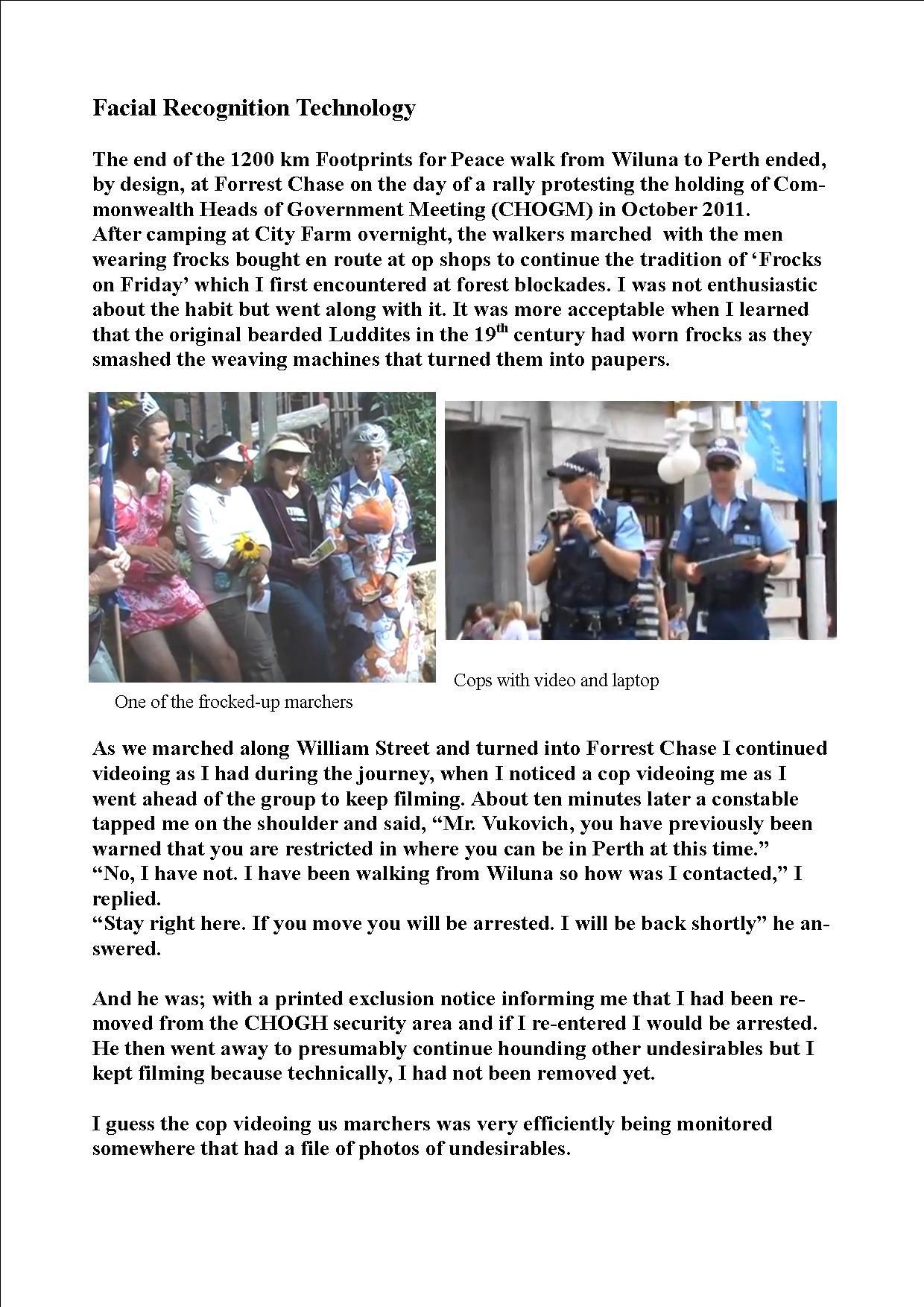

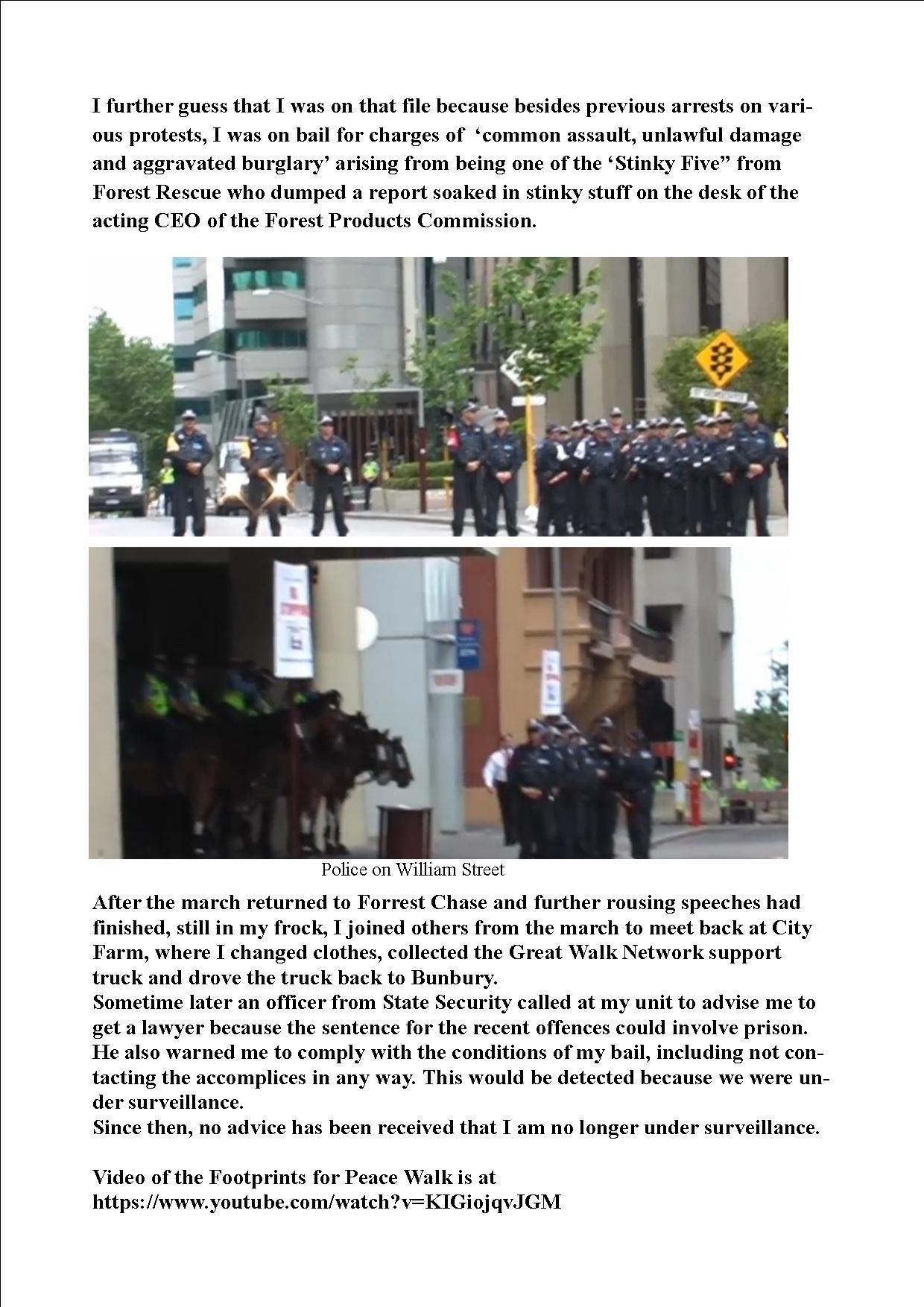

Facial Recognition Technology

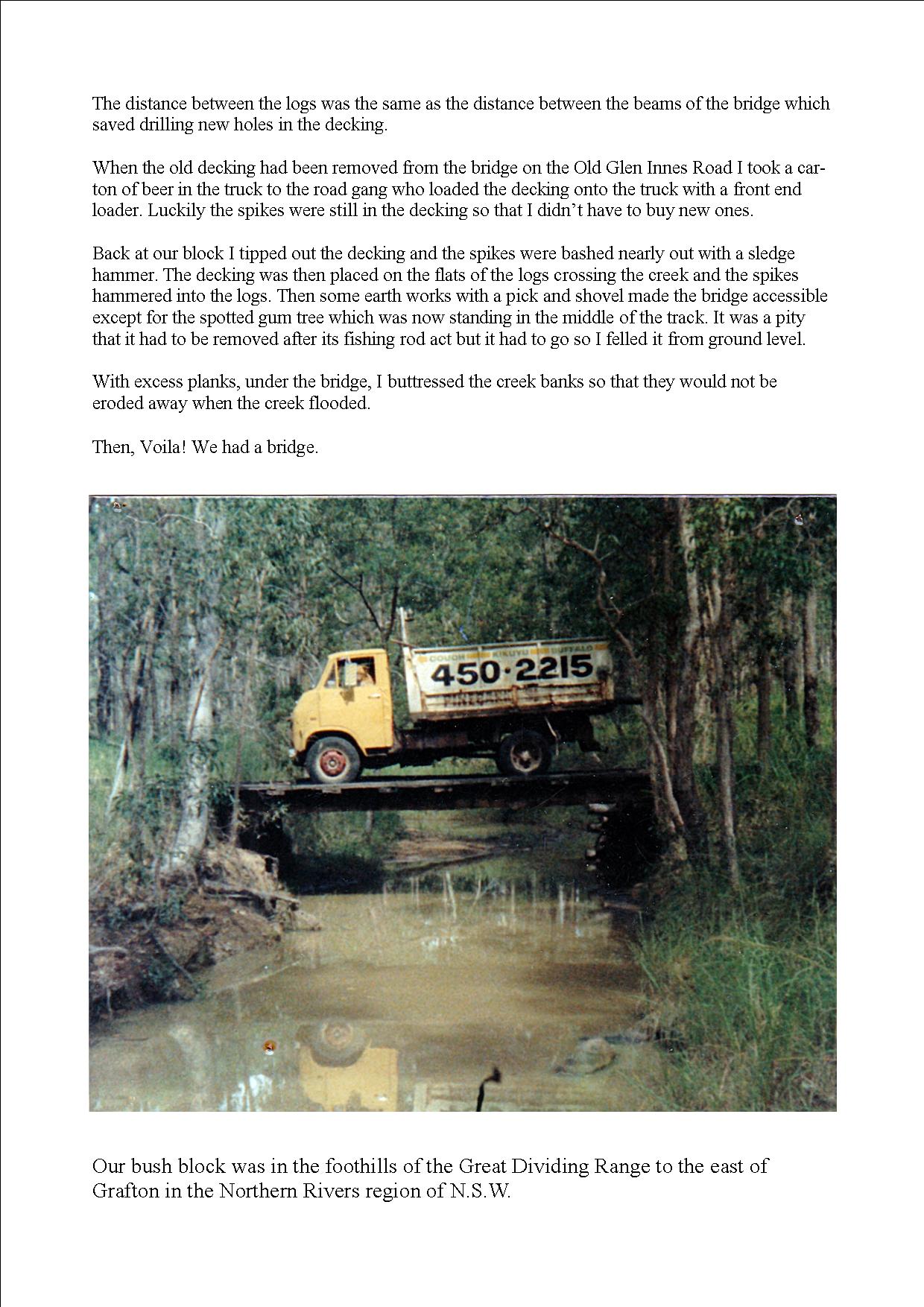

Bridge Building

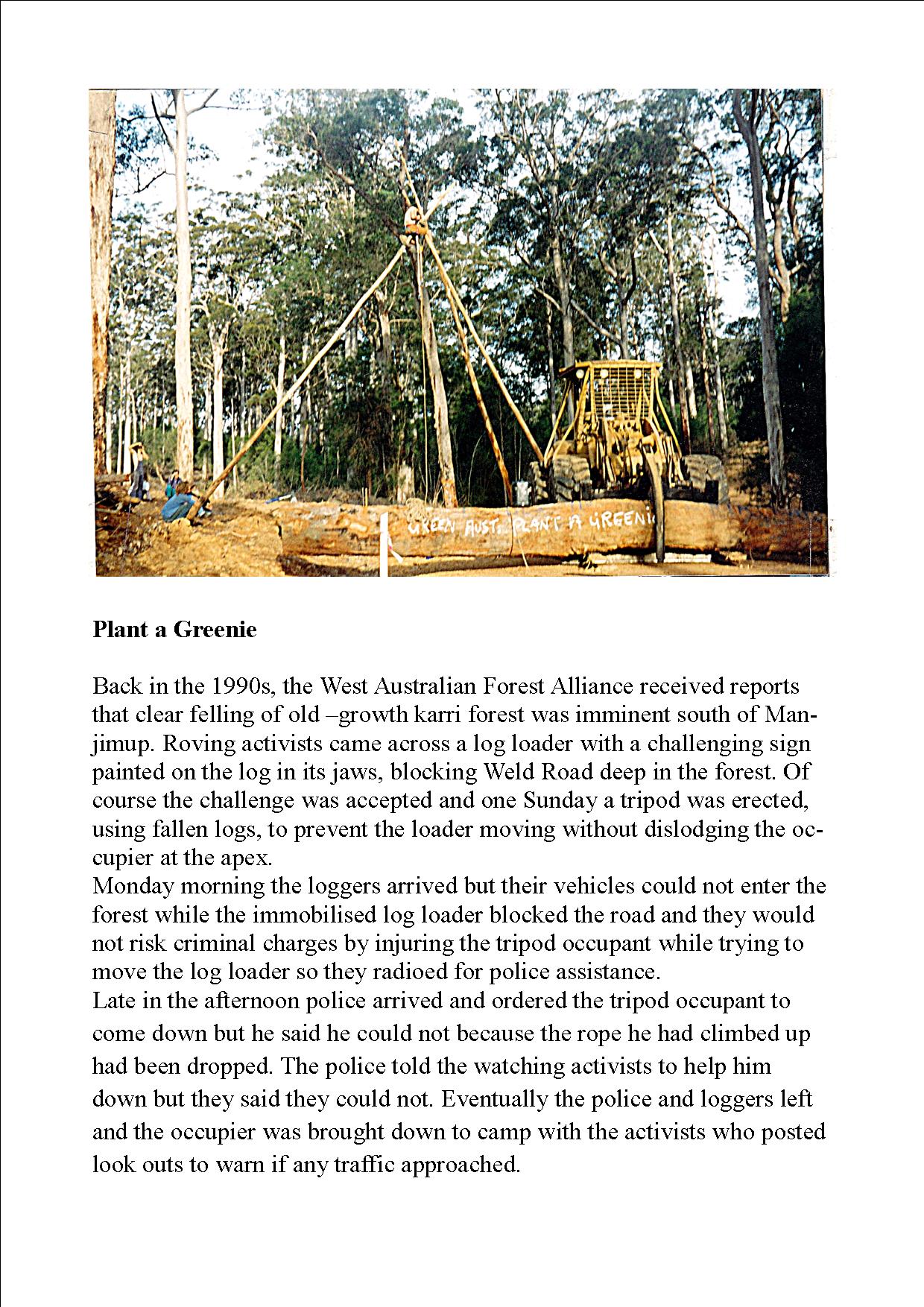

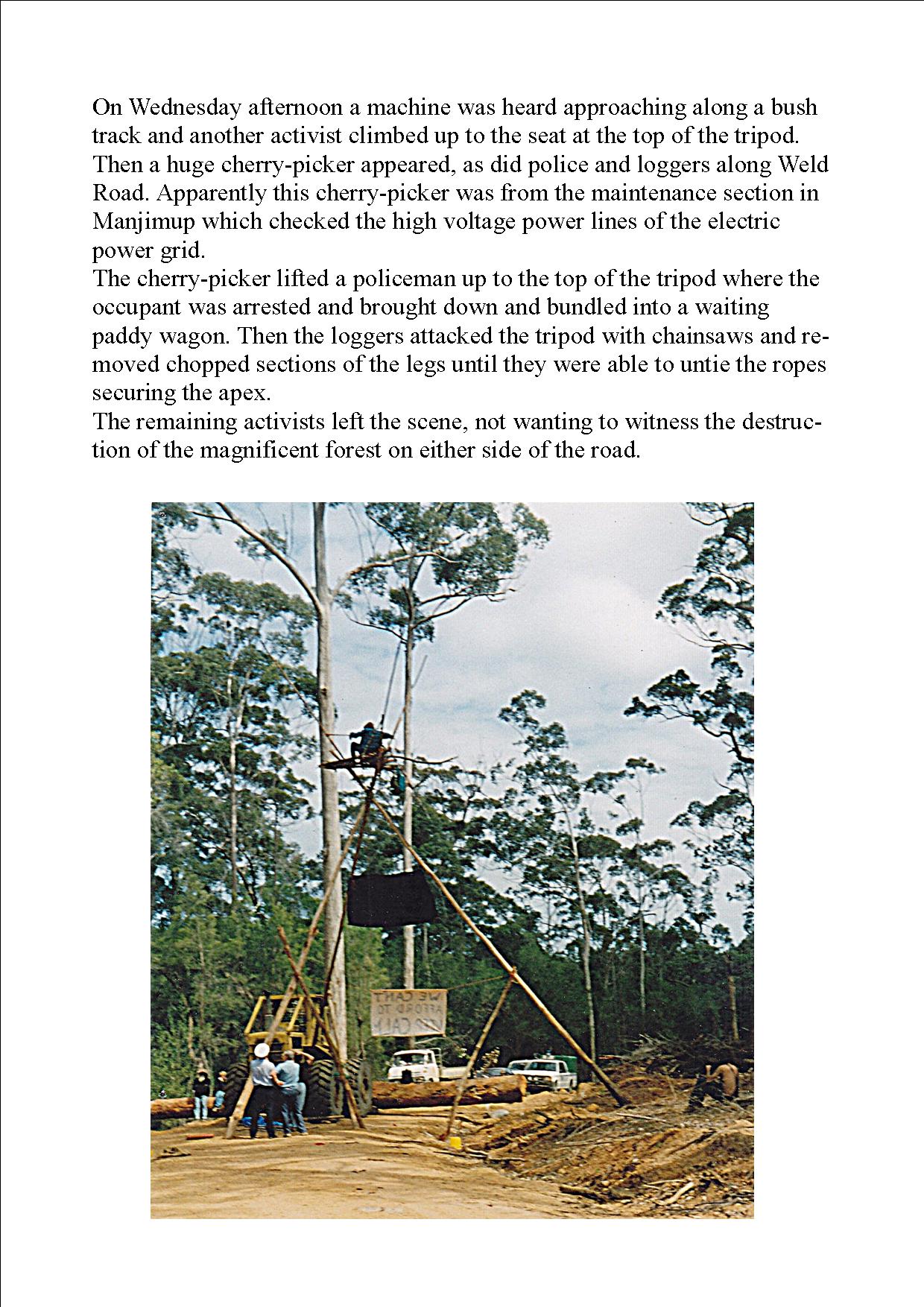

Plant a Greenie

Earth Garden Issue No. 50, May 1986

Earth Garden, Feb. 1986, Issue No. 49

Cruise of the ‘Kiwi’ Pt. 1

Glug, Glug.

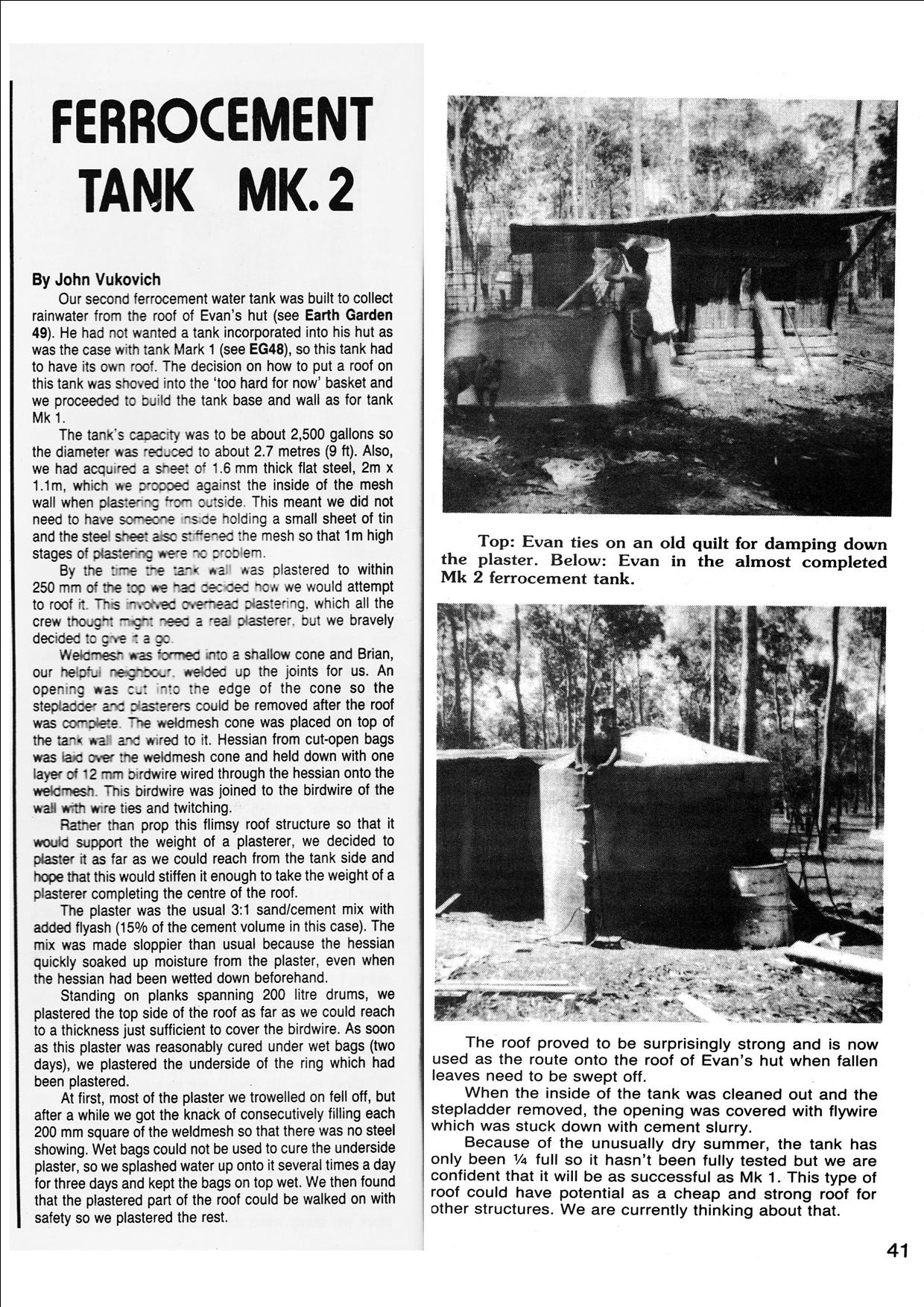

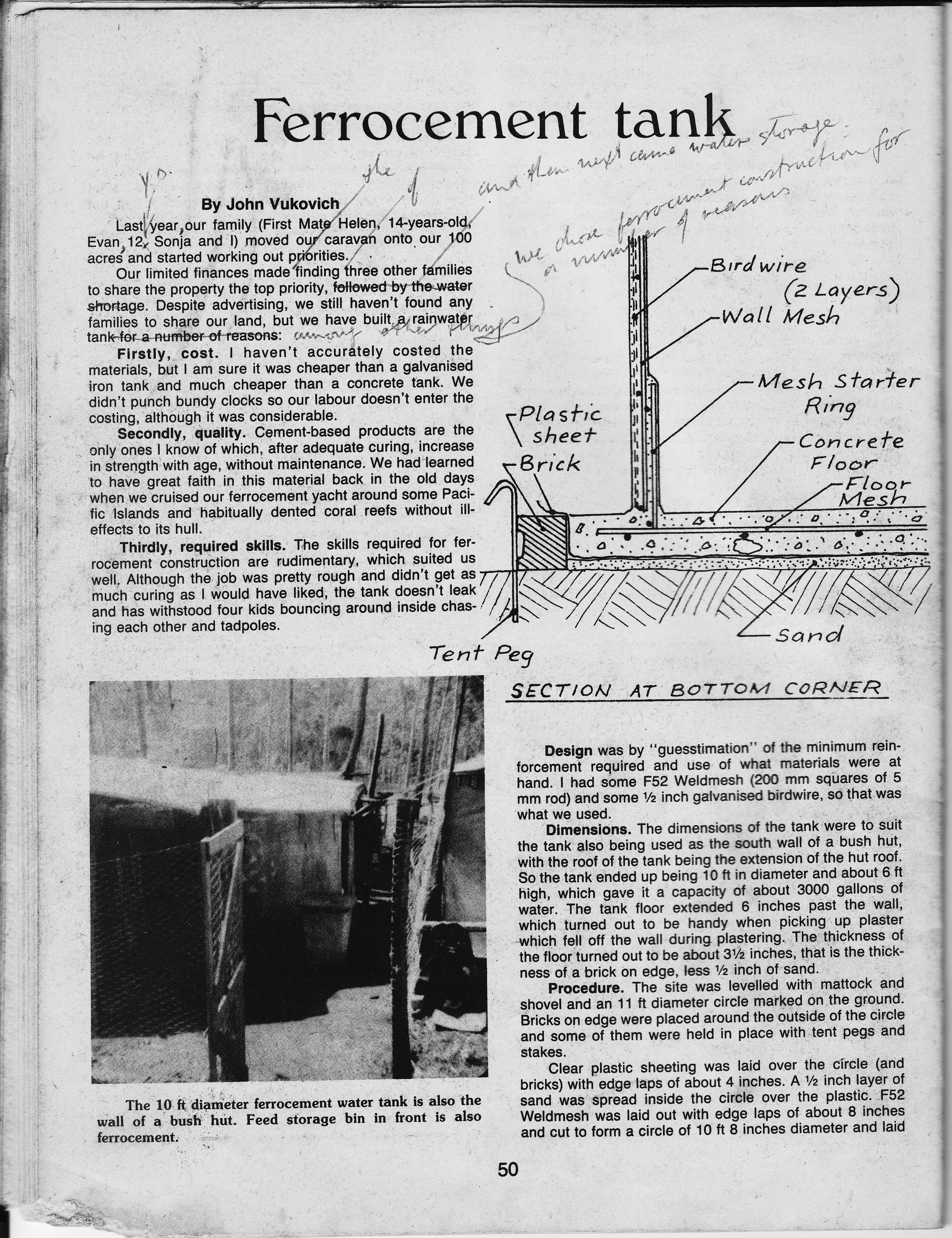

Ferrocement water tank

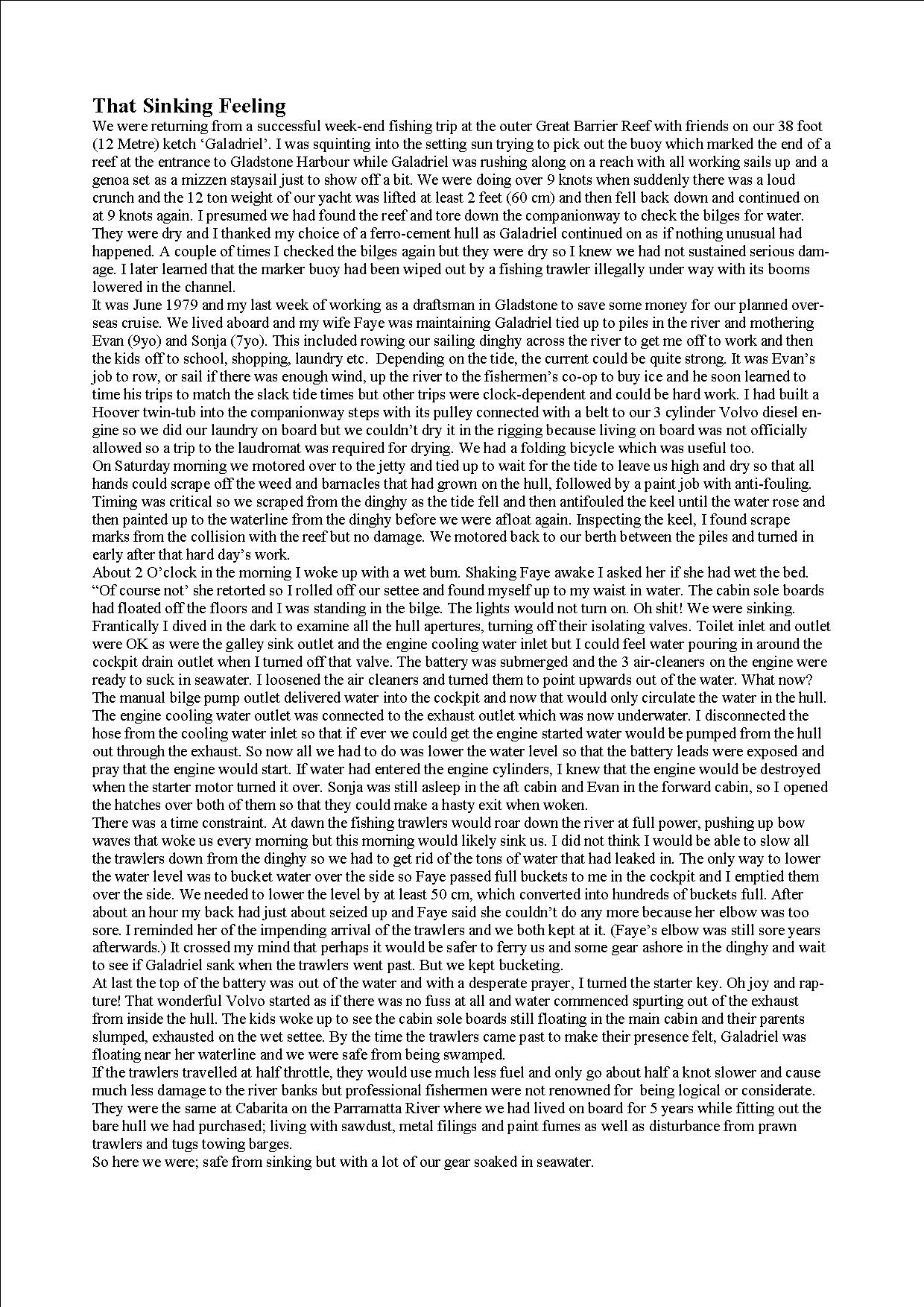

That Sinking Feeling

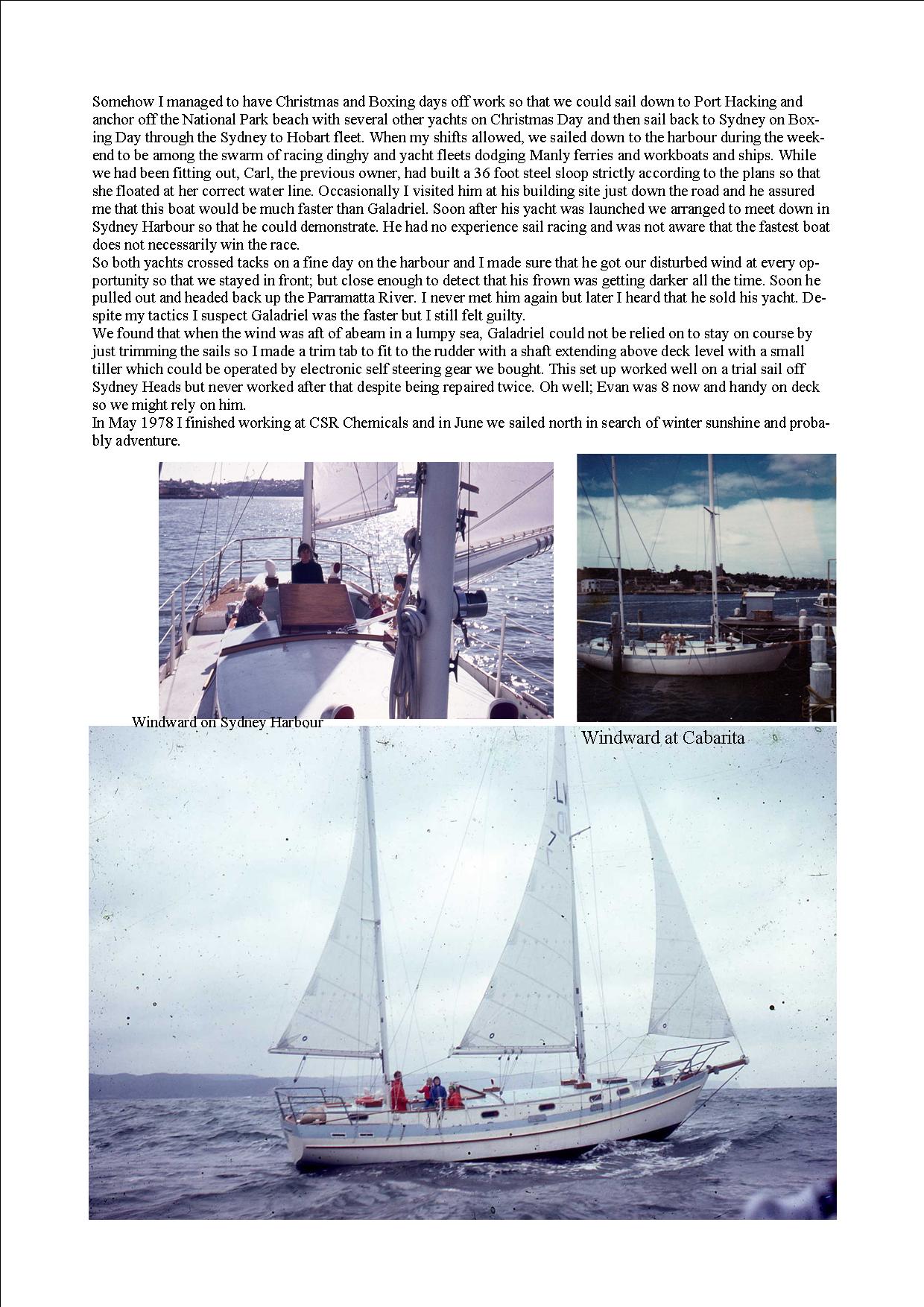

Acquiring ‘Galadriel’

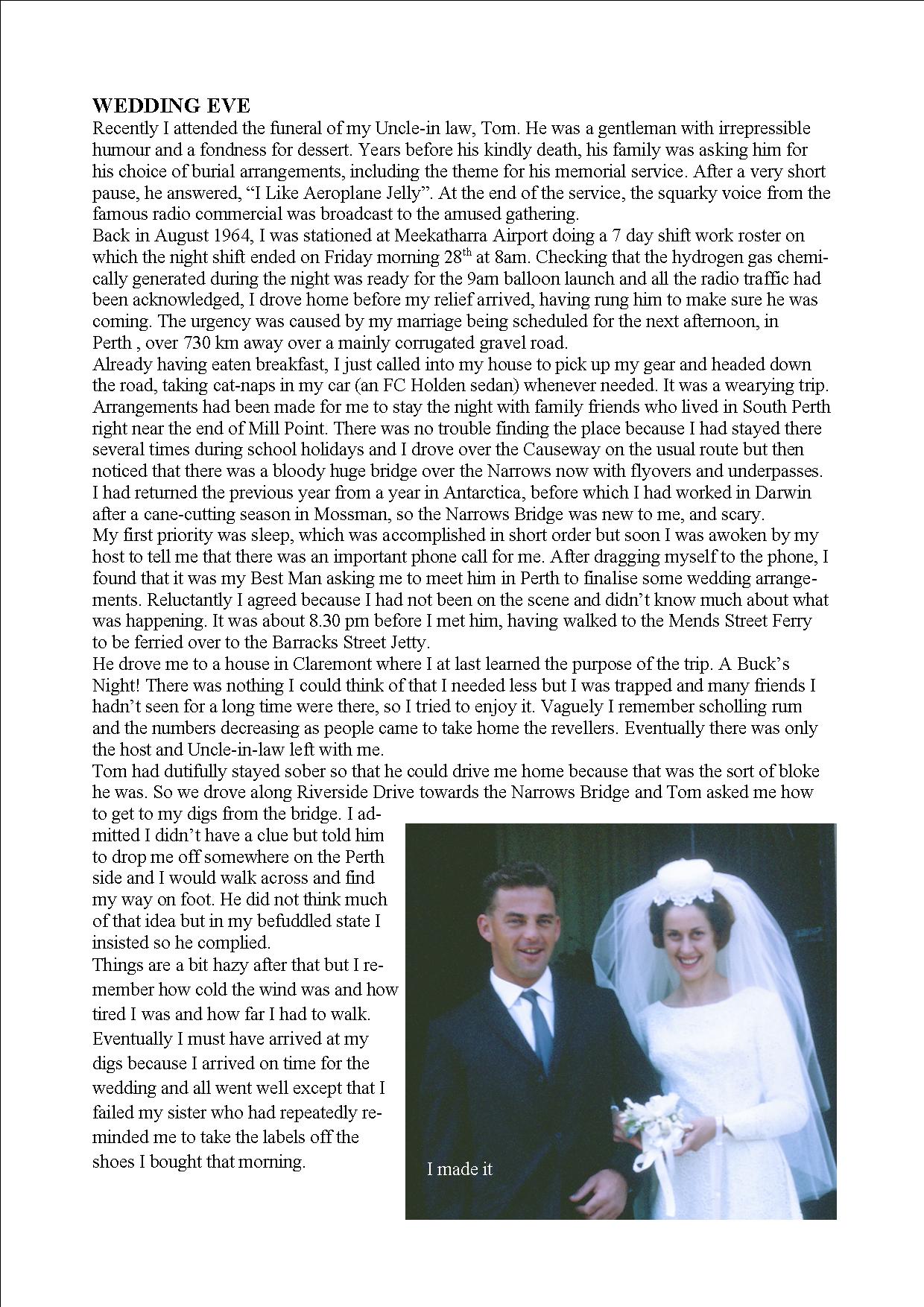

Wedding Eve

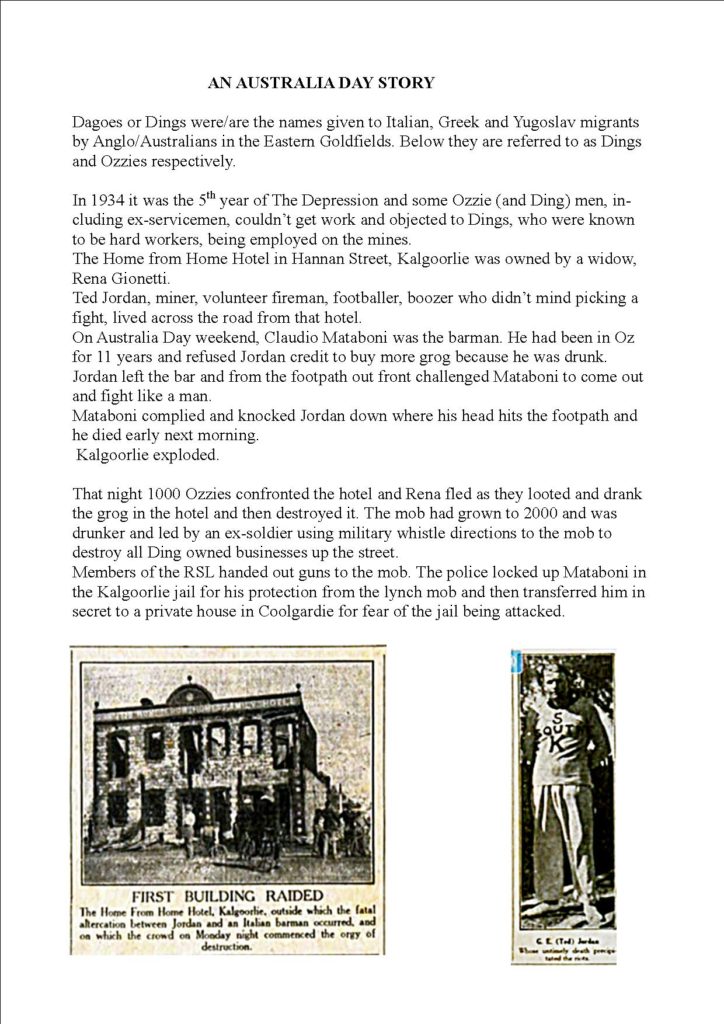

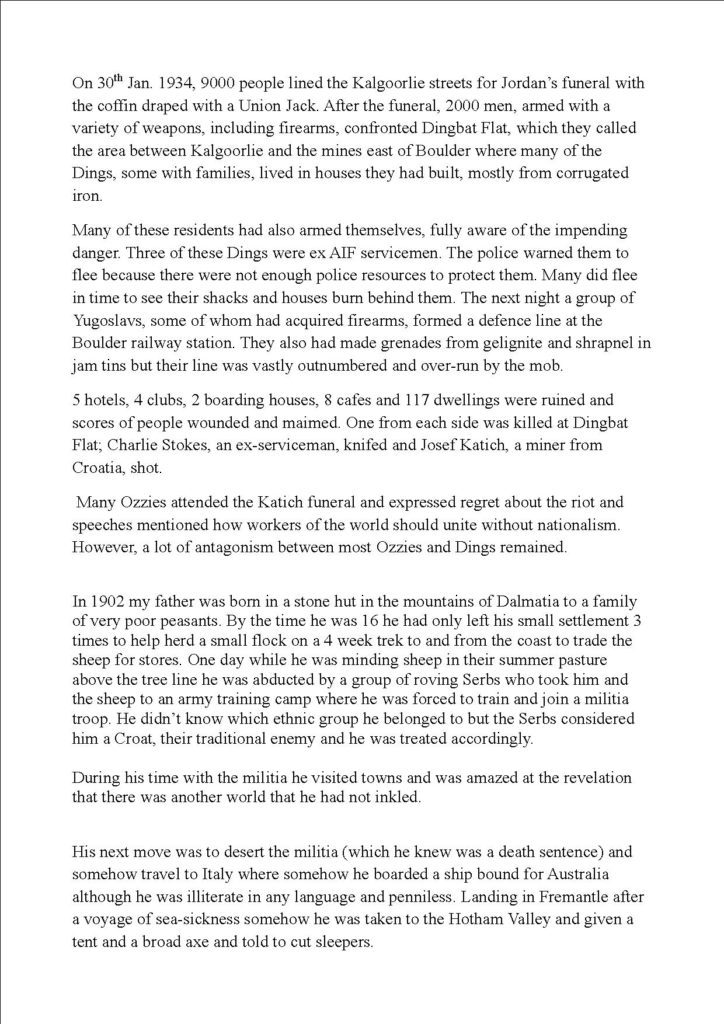

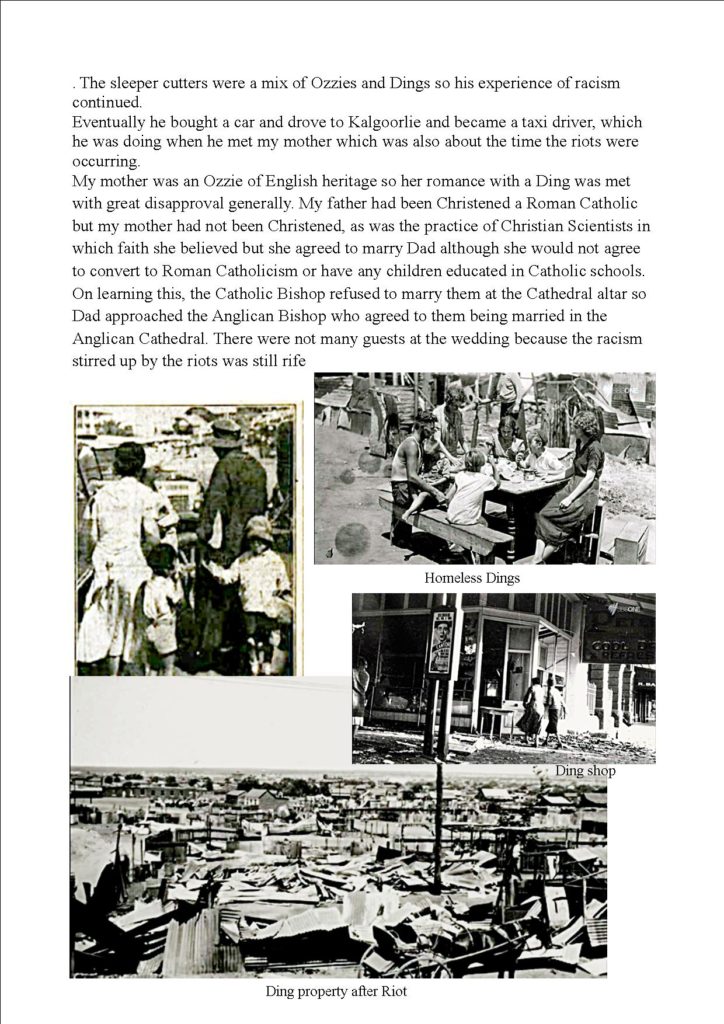

Australia Day

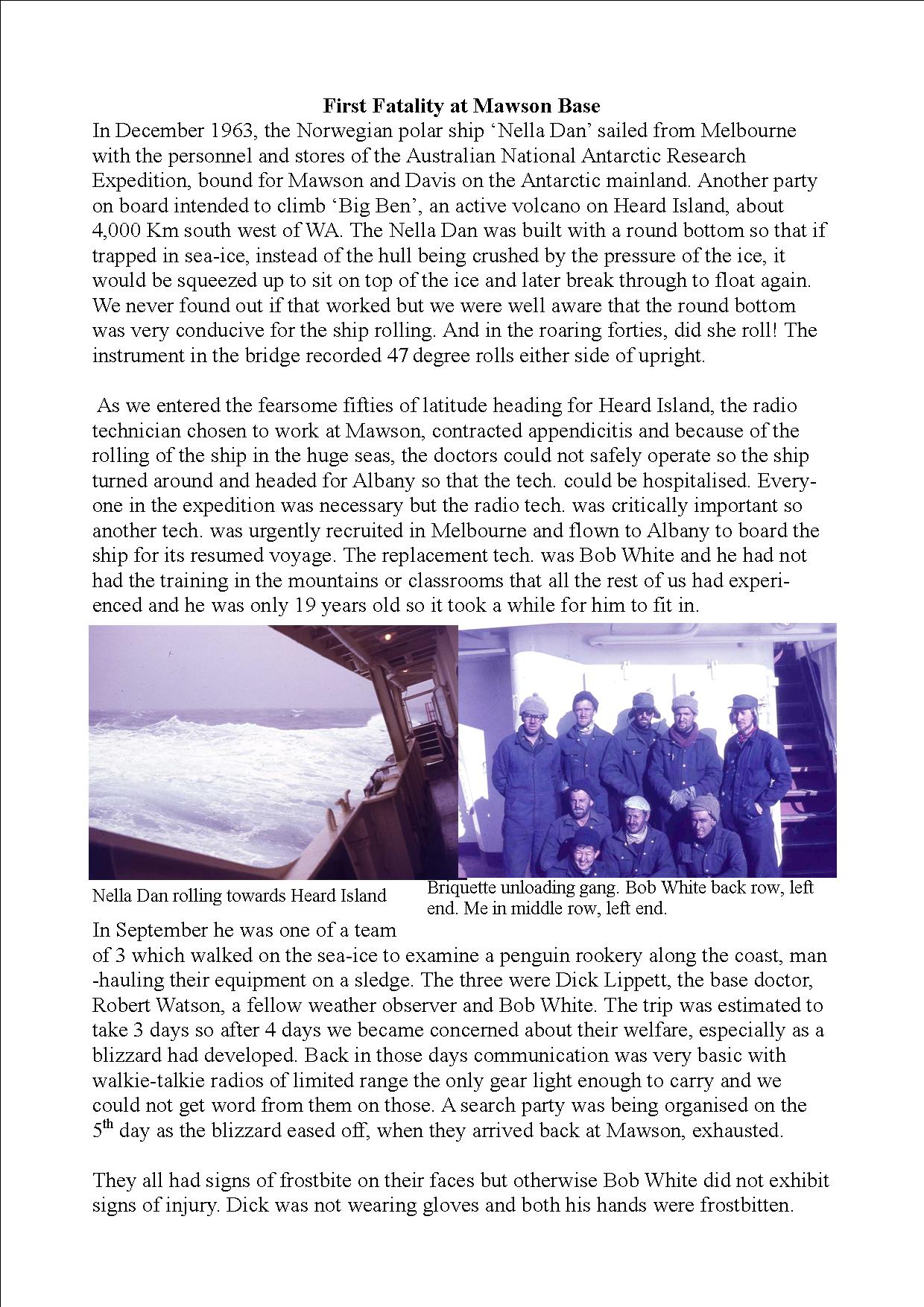

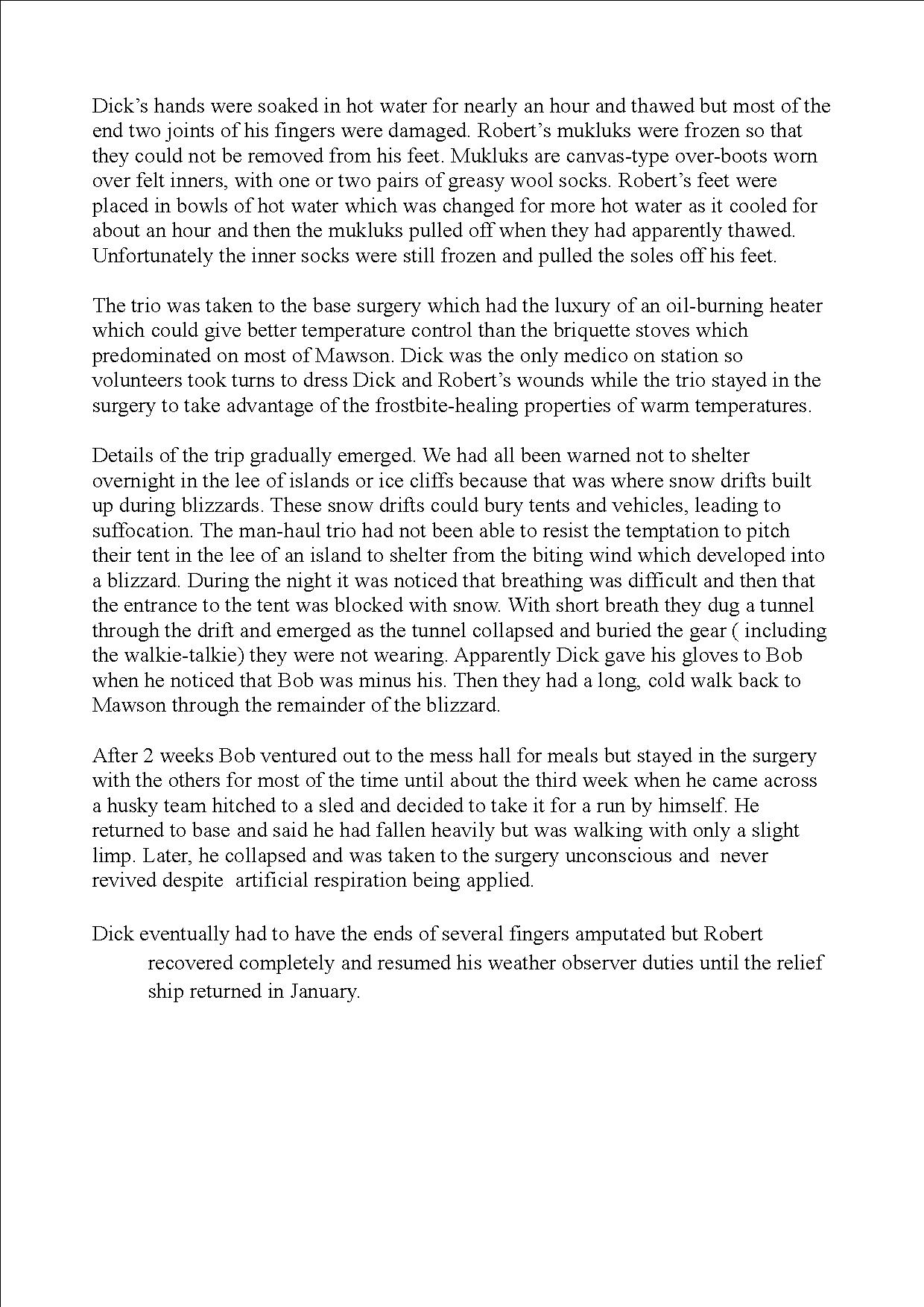

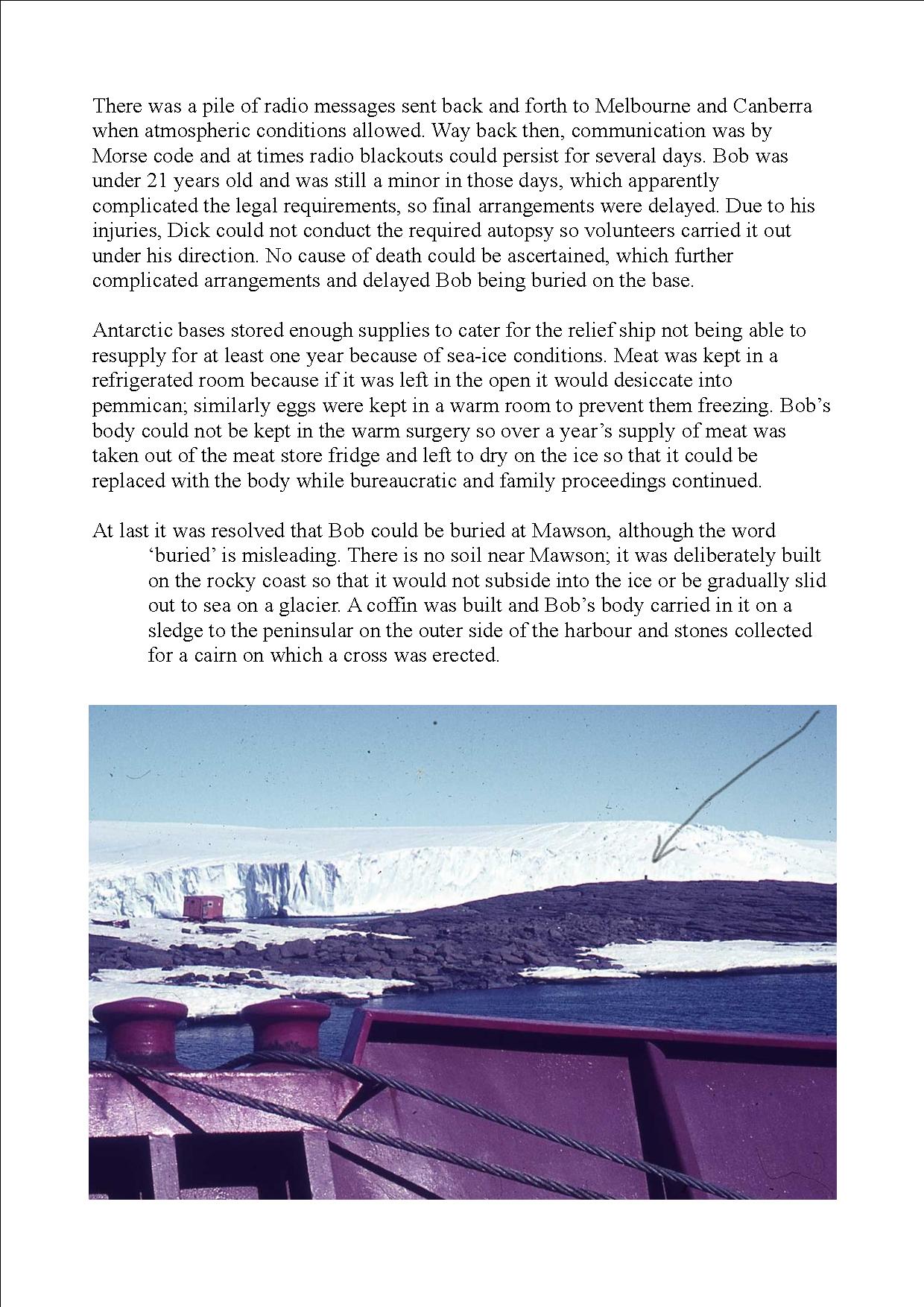

First Fatality at Mawson Base

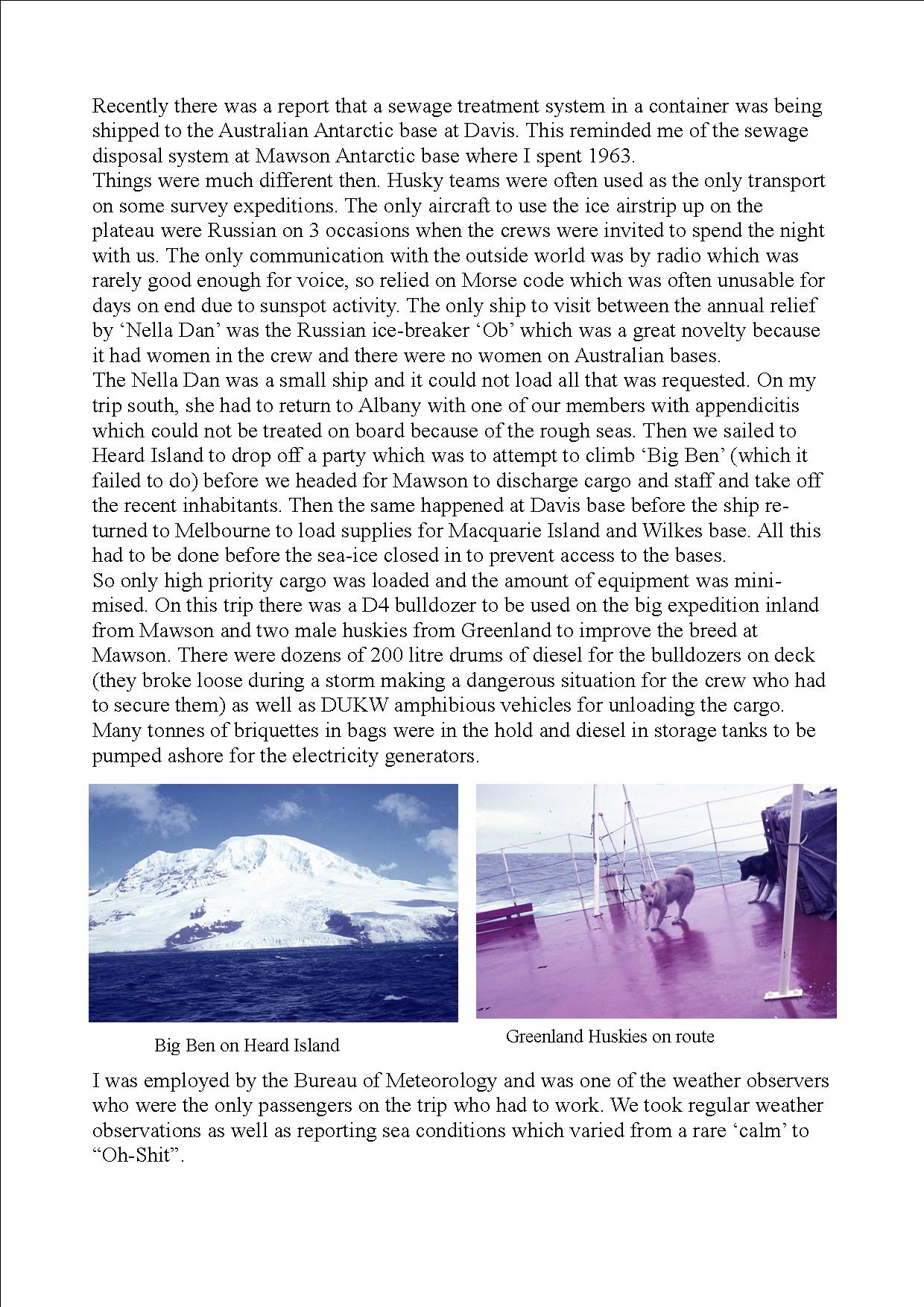

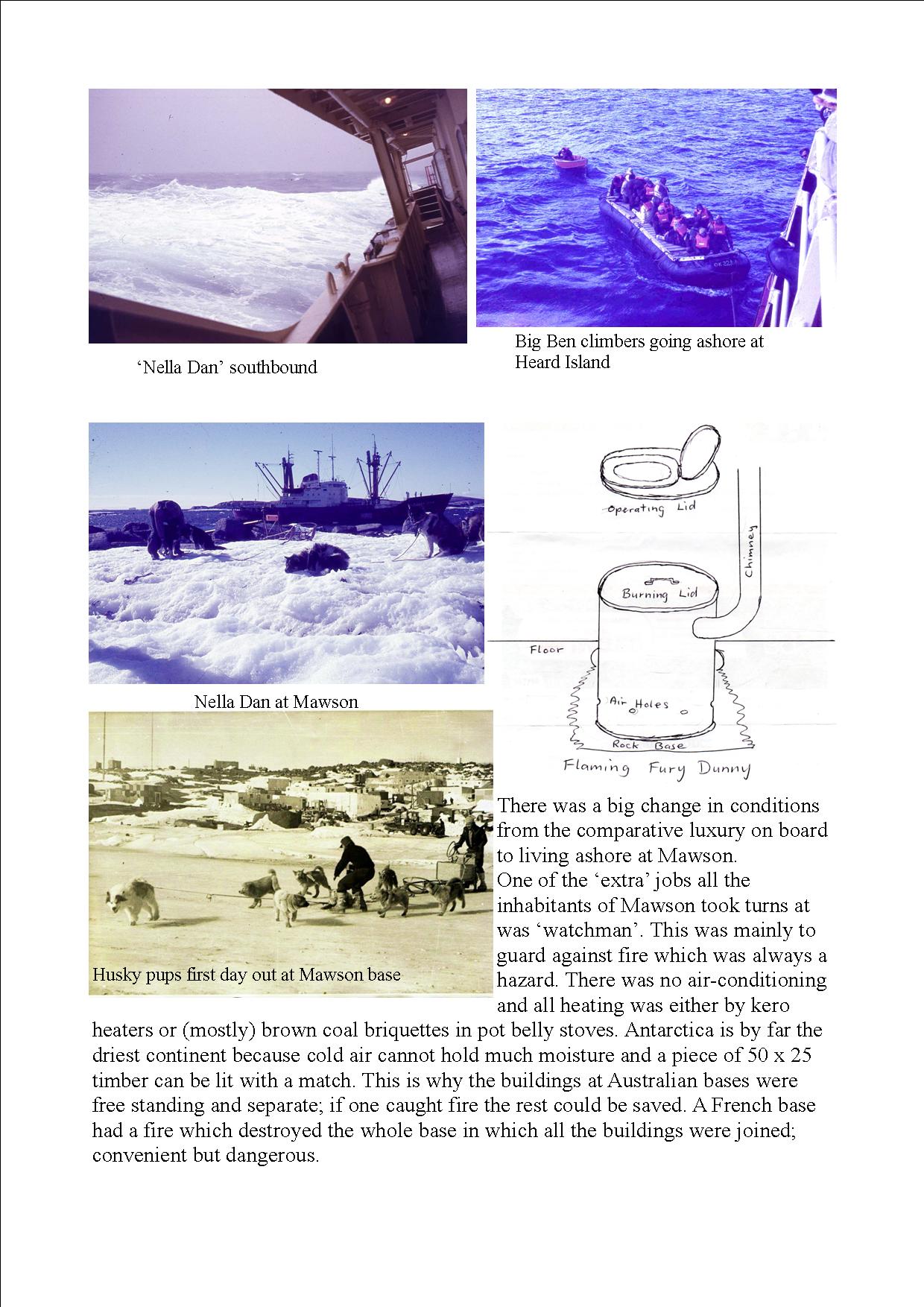

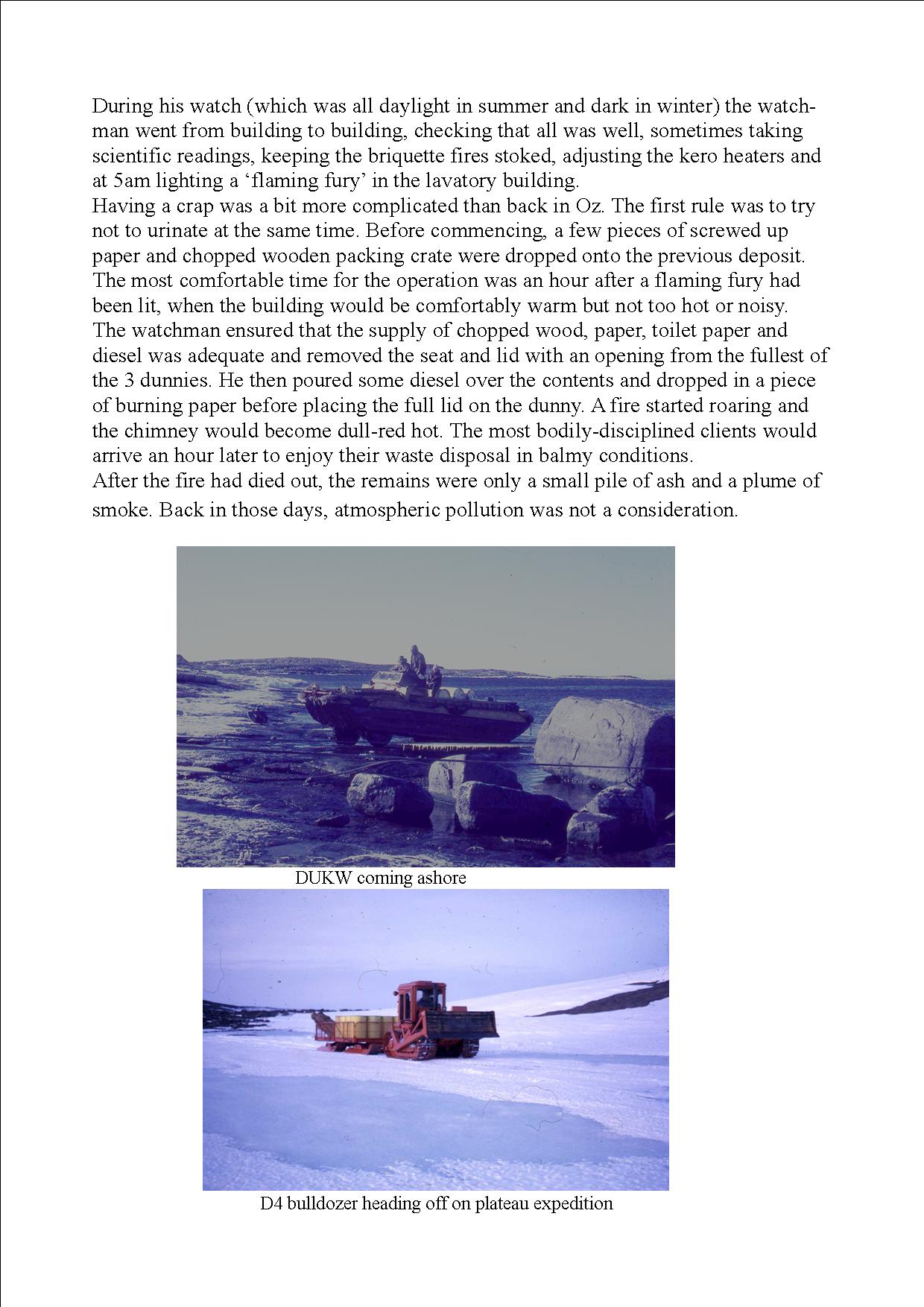

Flaming Furies

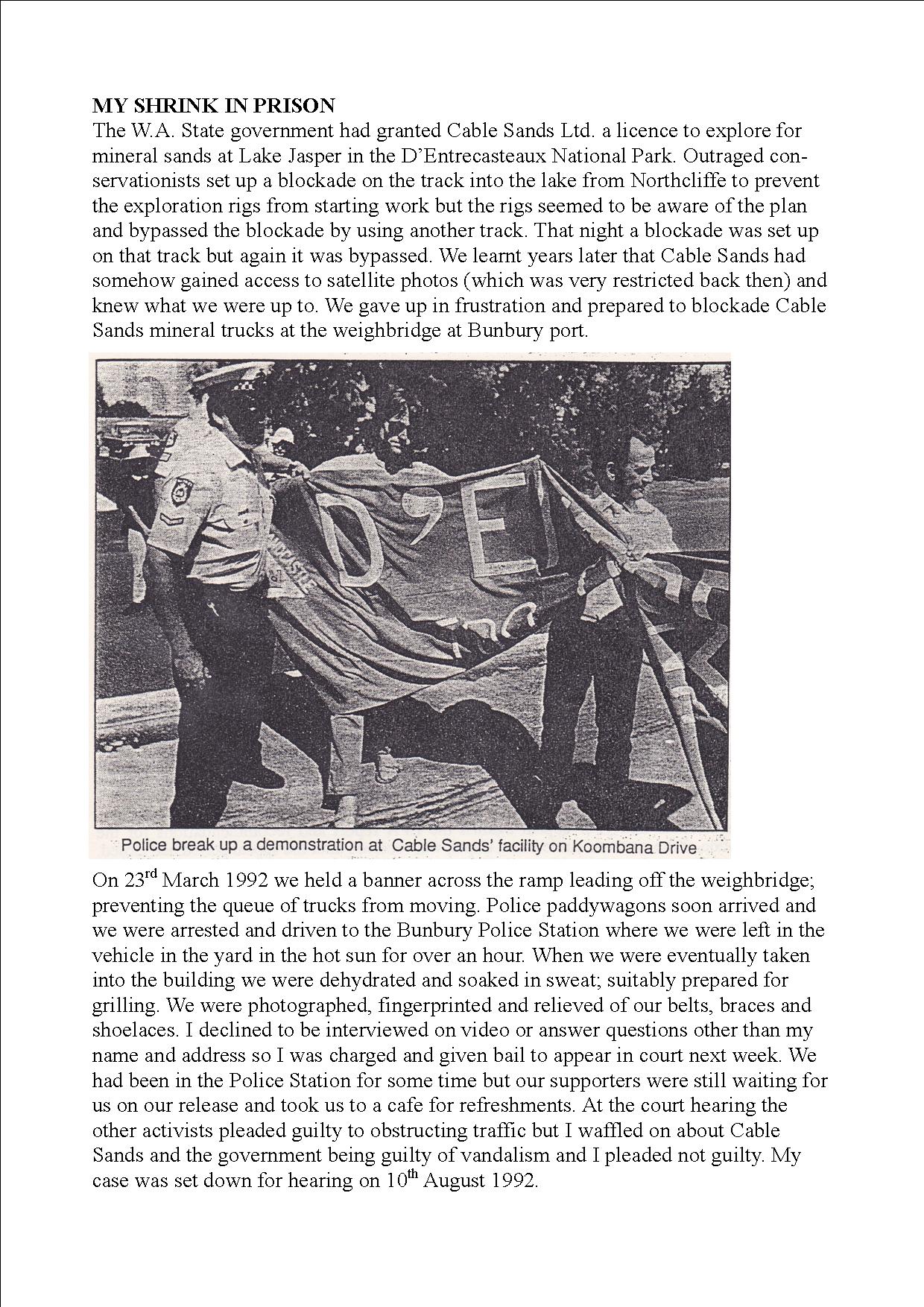

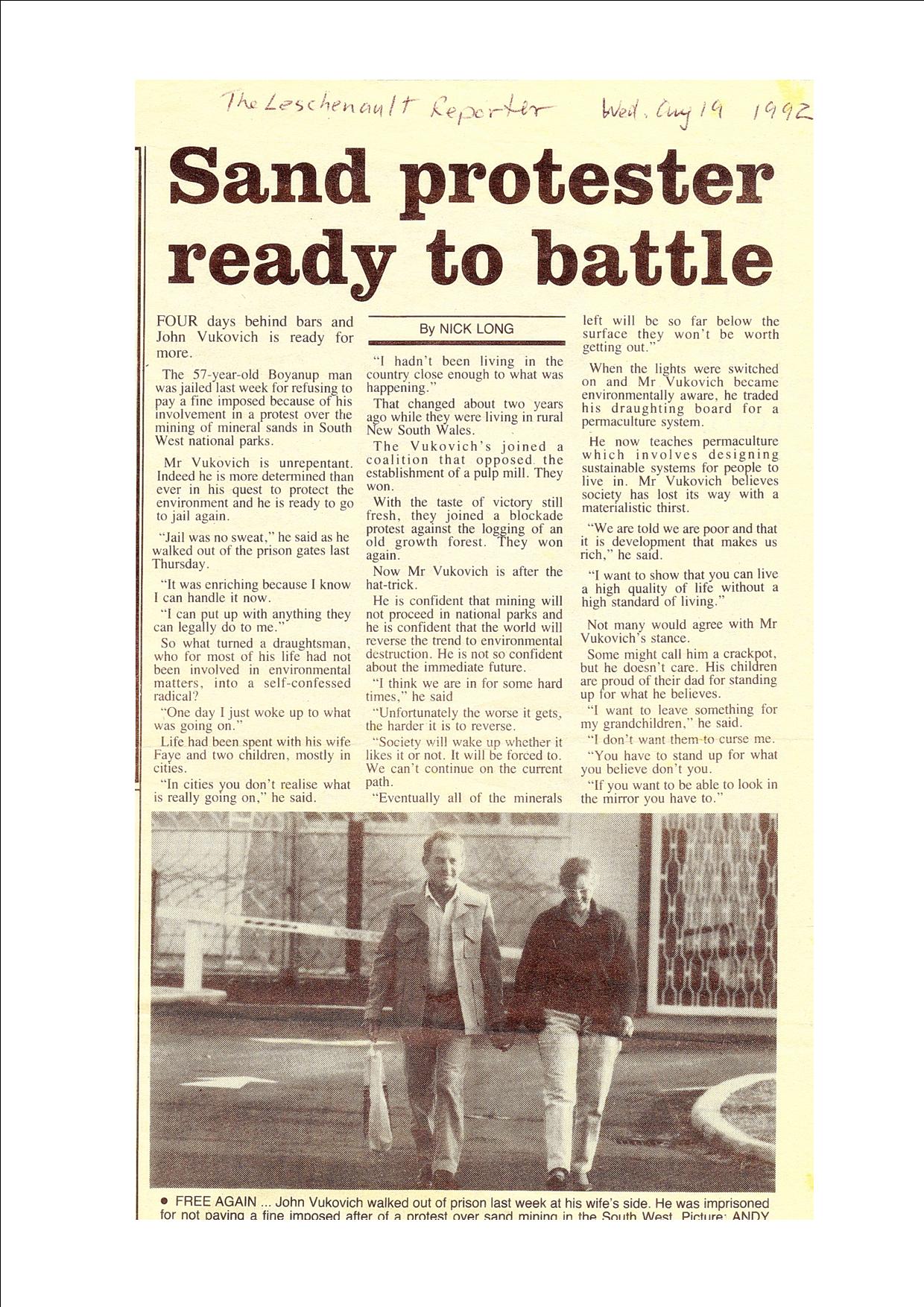

My Shrink in Prison

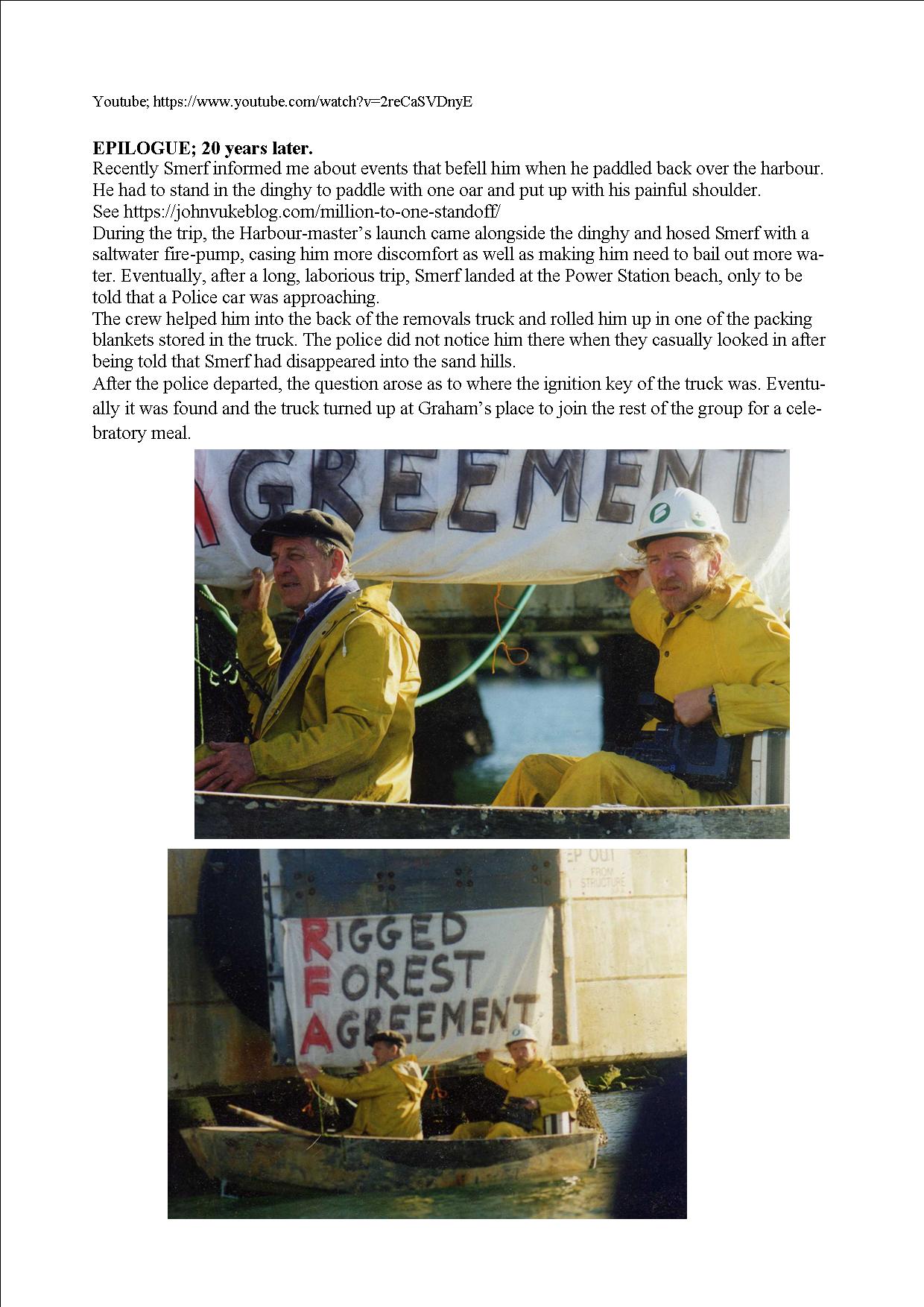

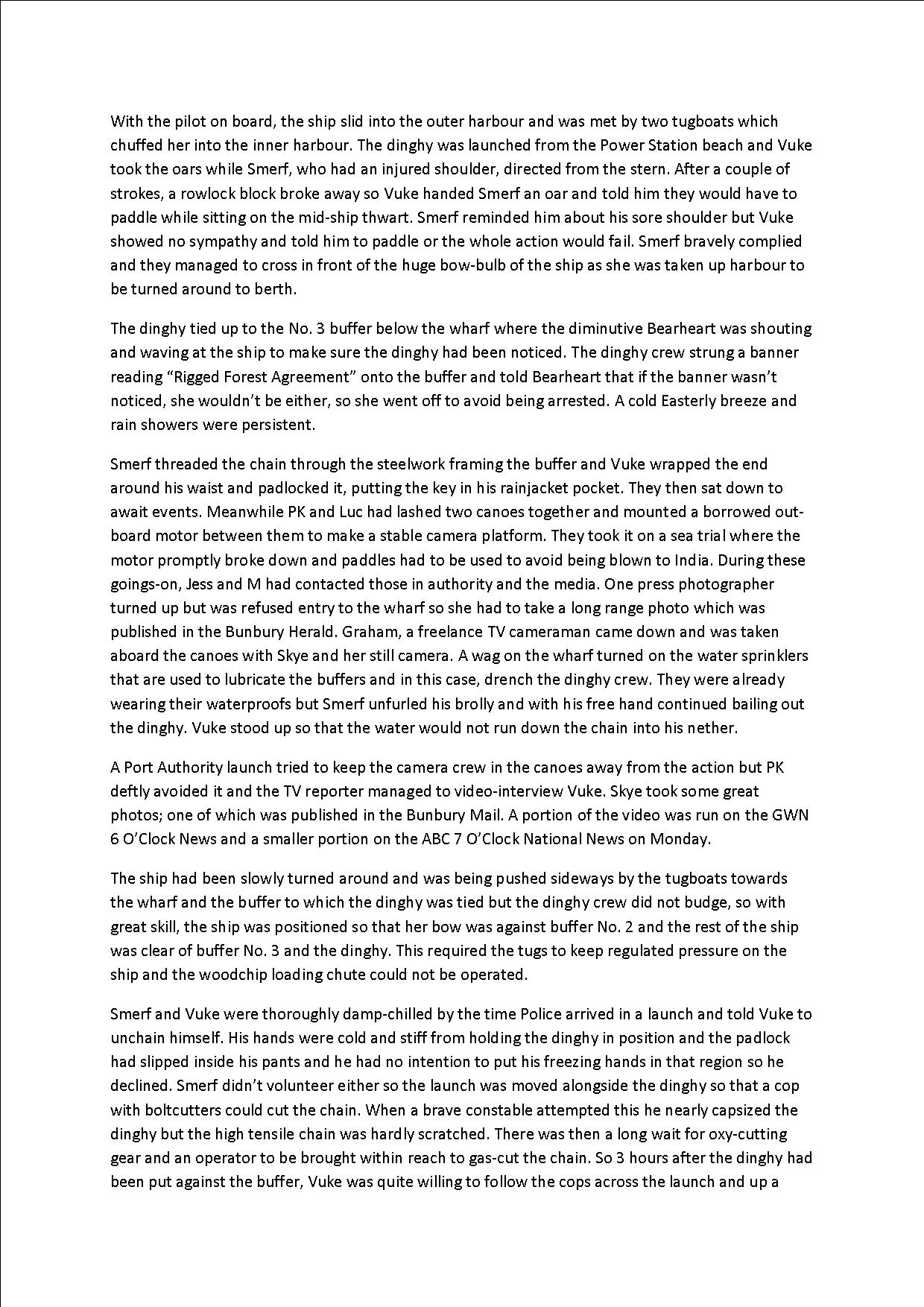

Million to One Standoff

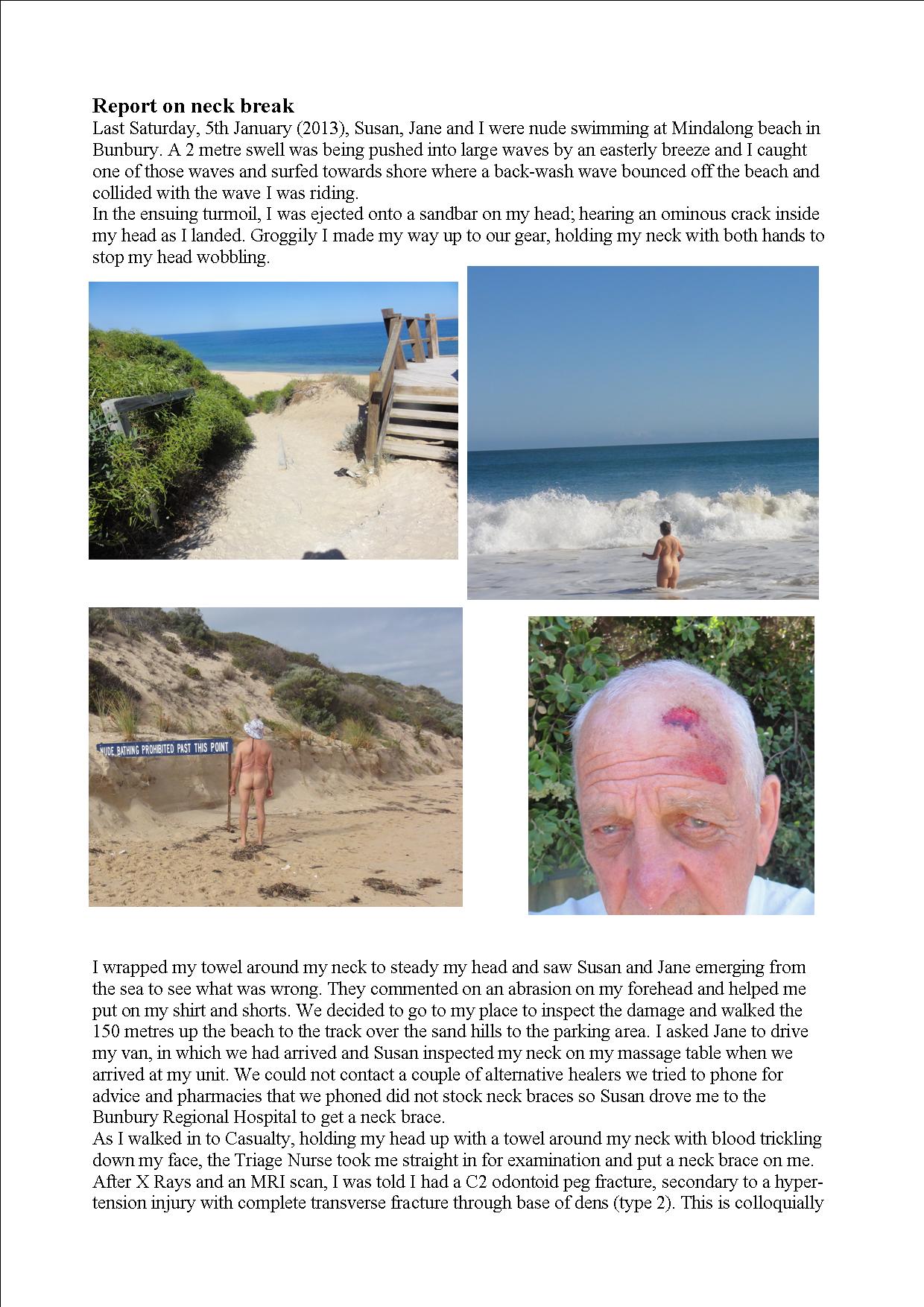

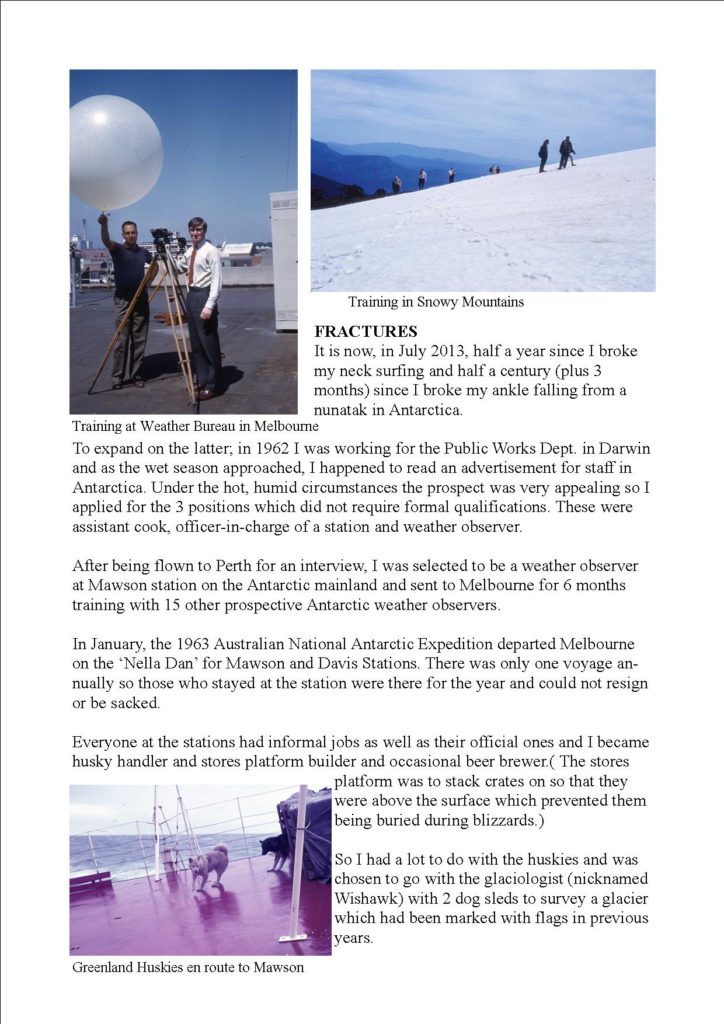

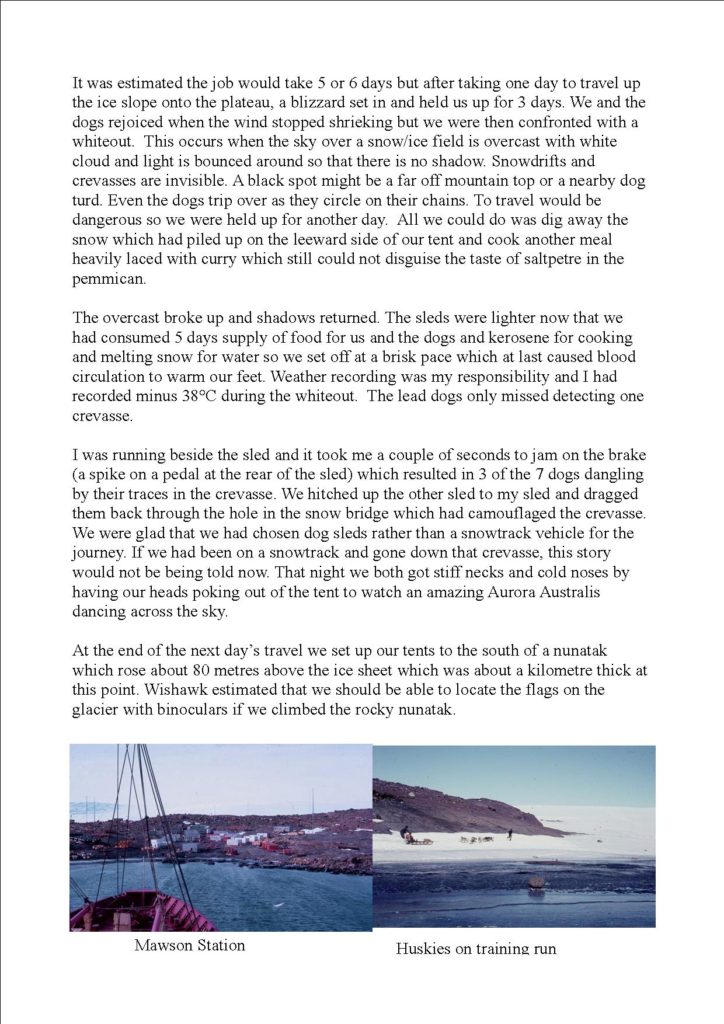

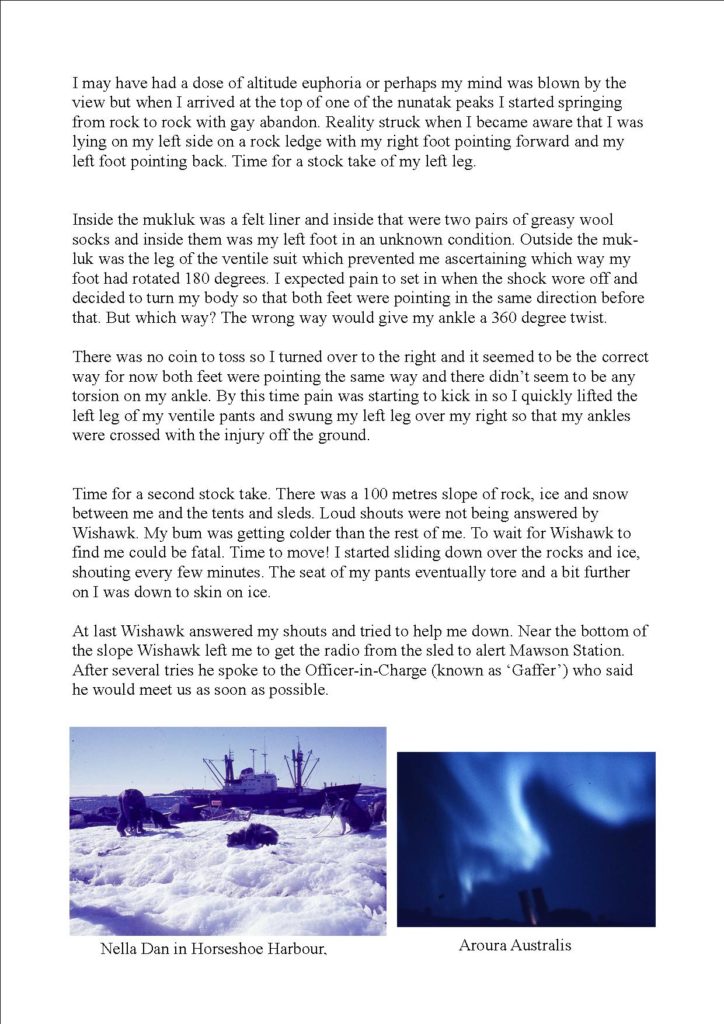

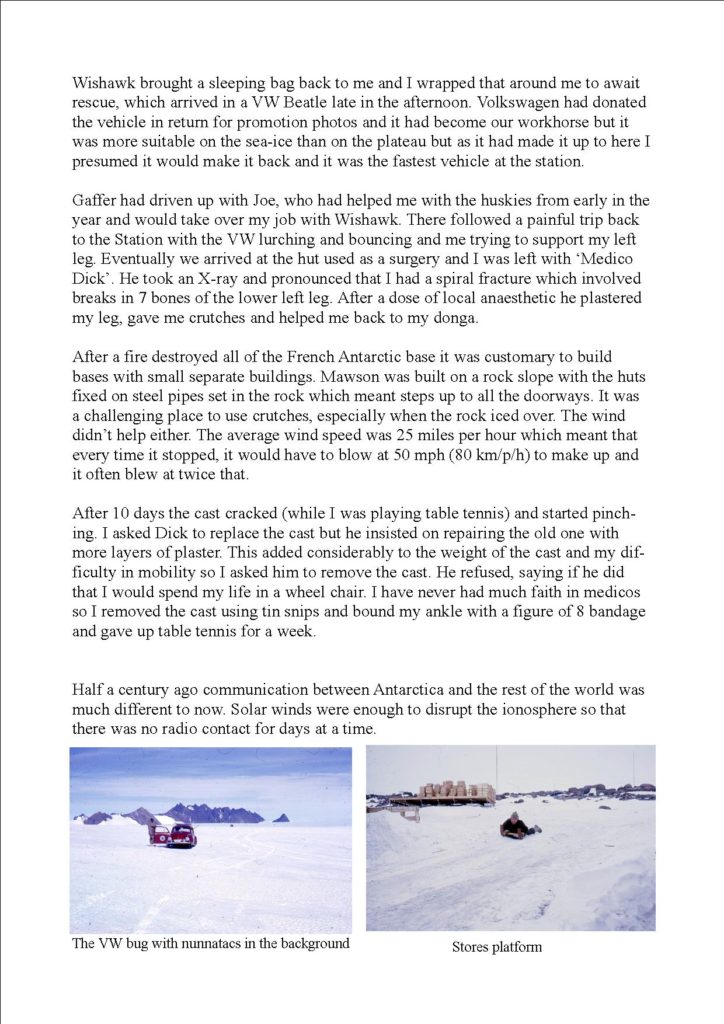

Fractures

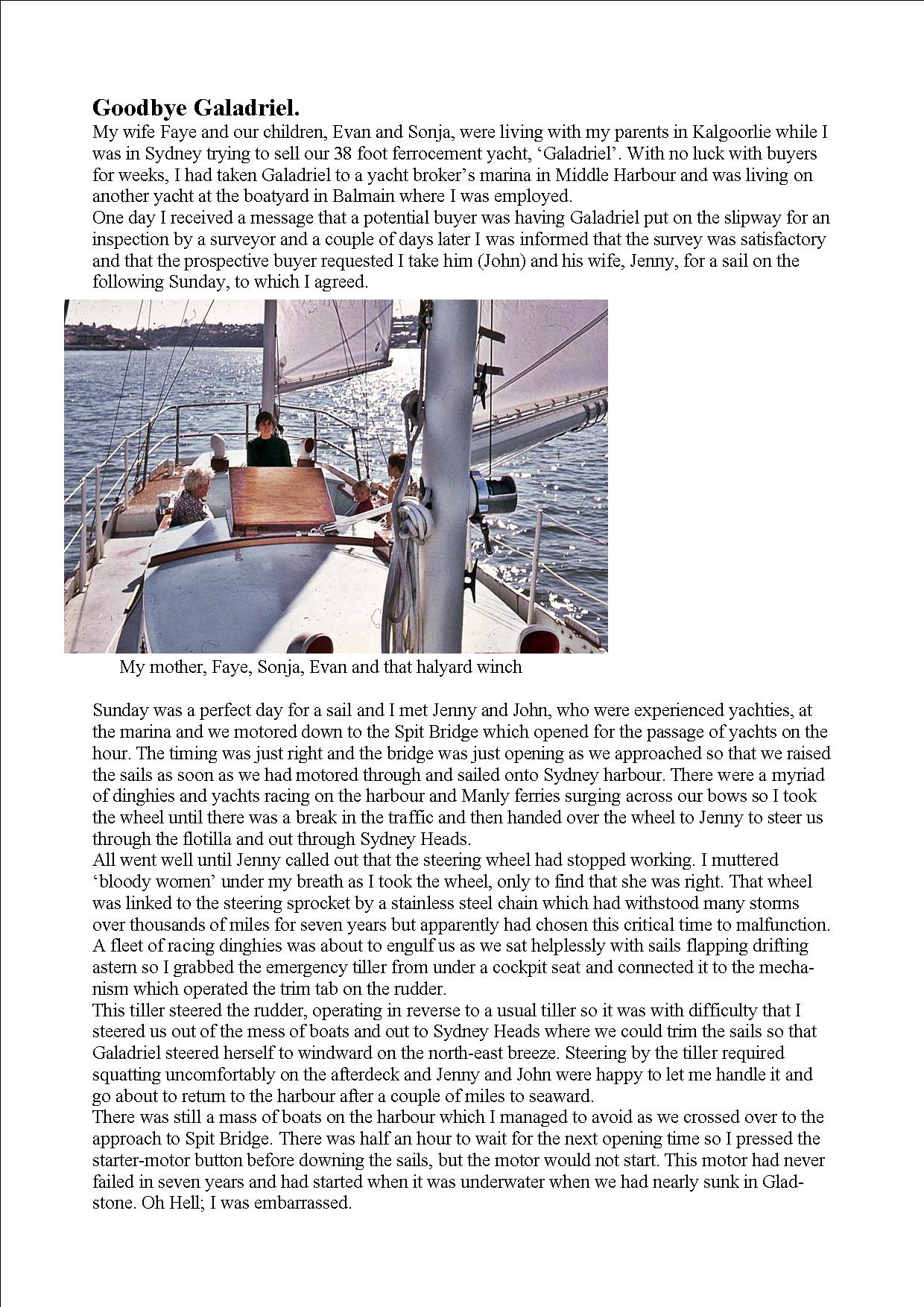

Goodbye Galadriel

Return via Italy

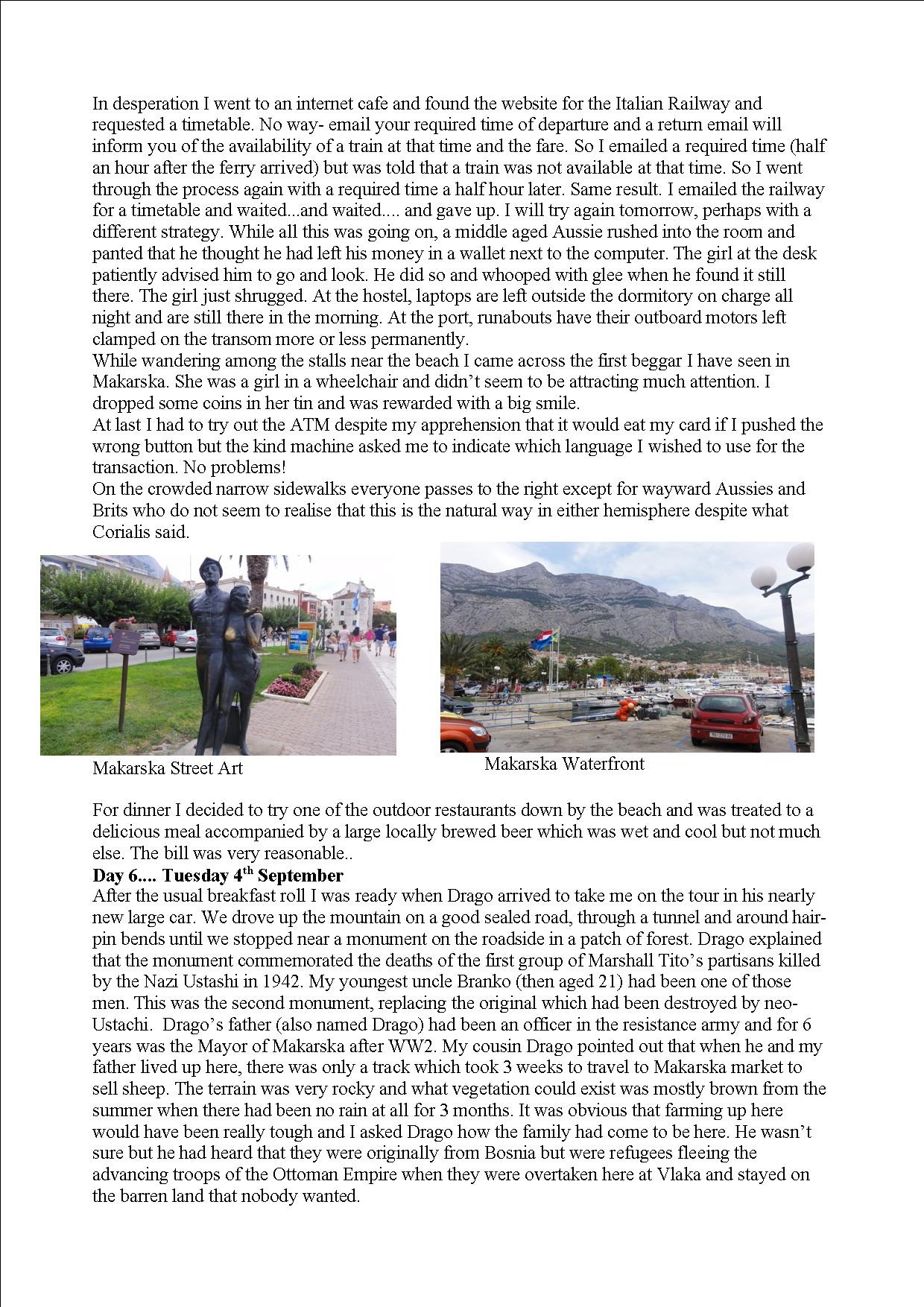

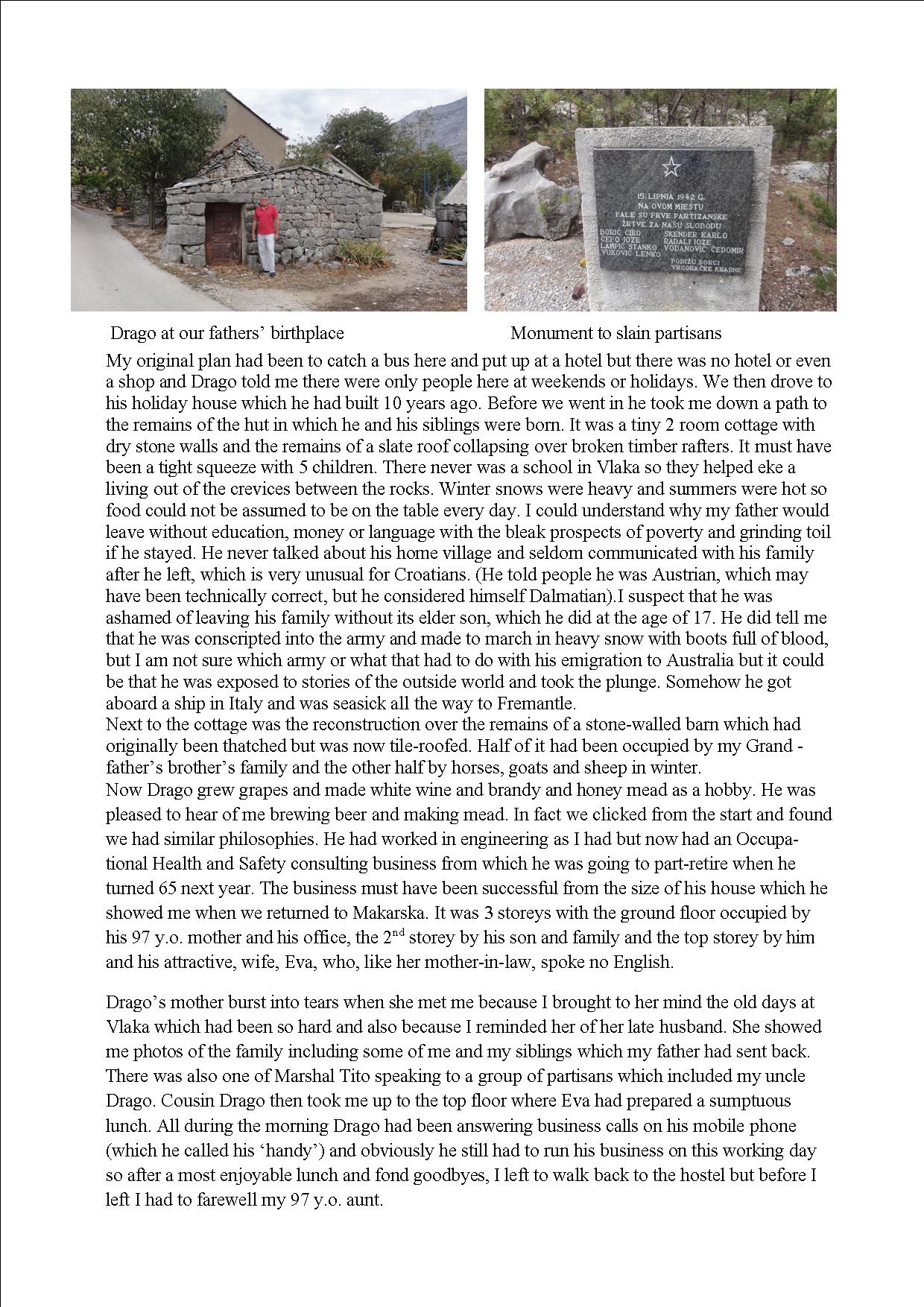

Trip to Croatia

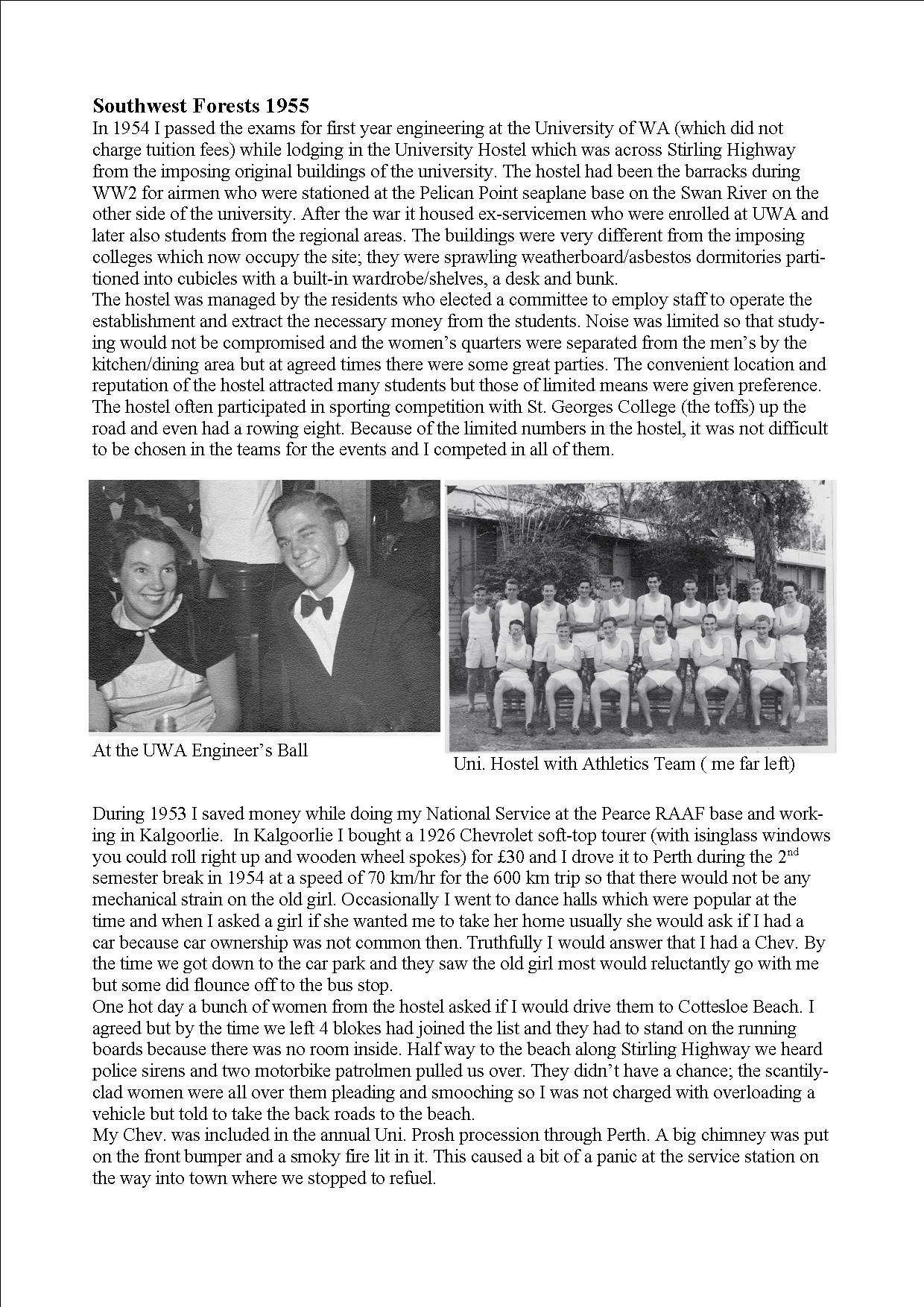

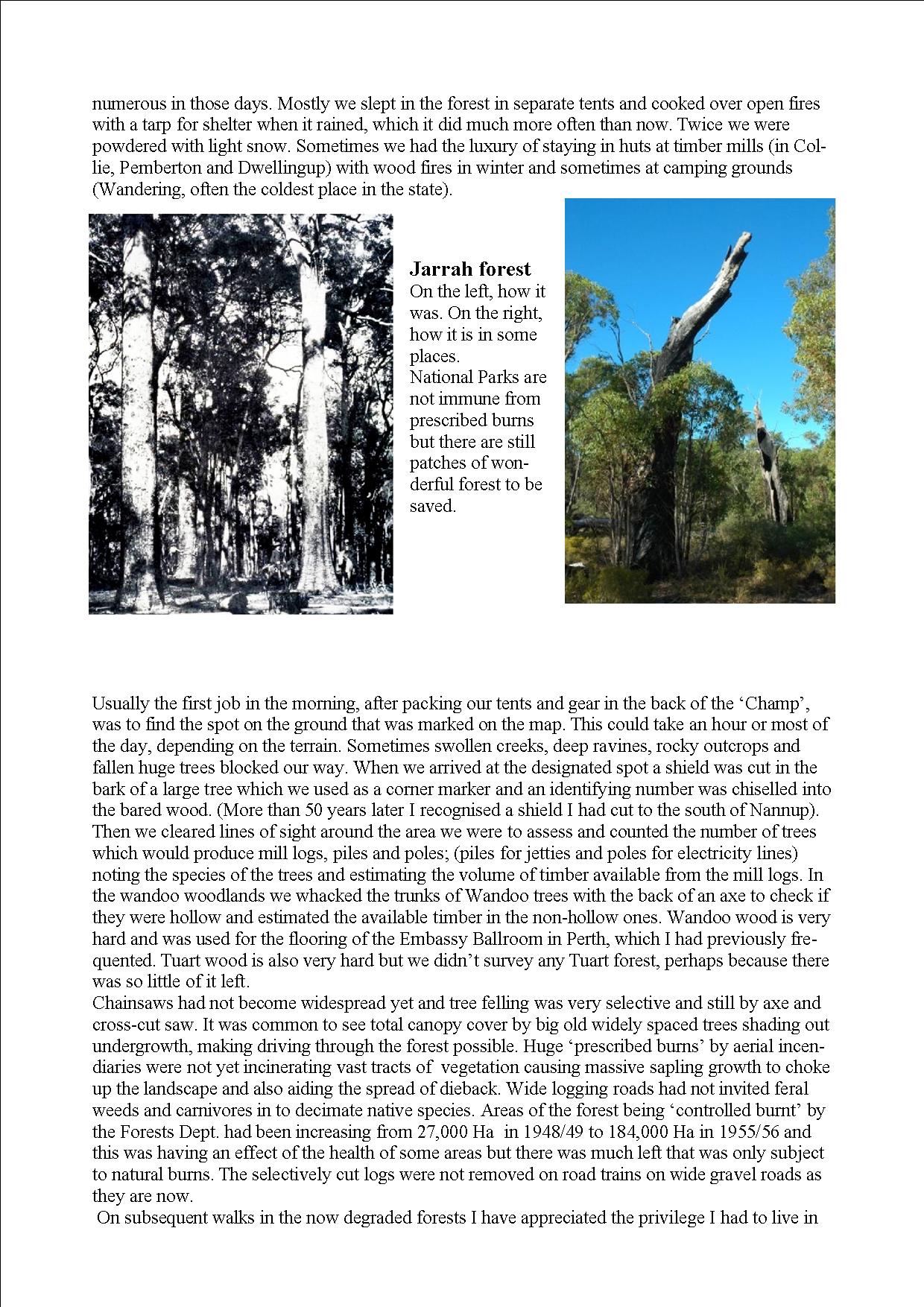

Southwest forests 1955

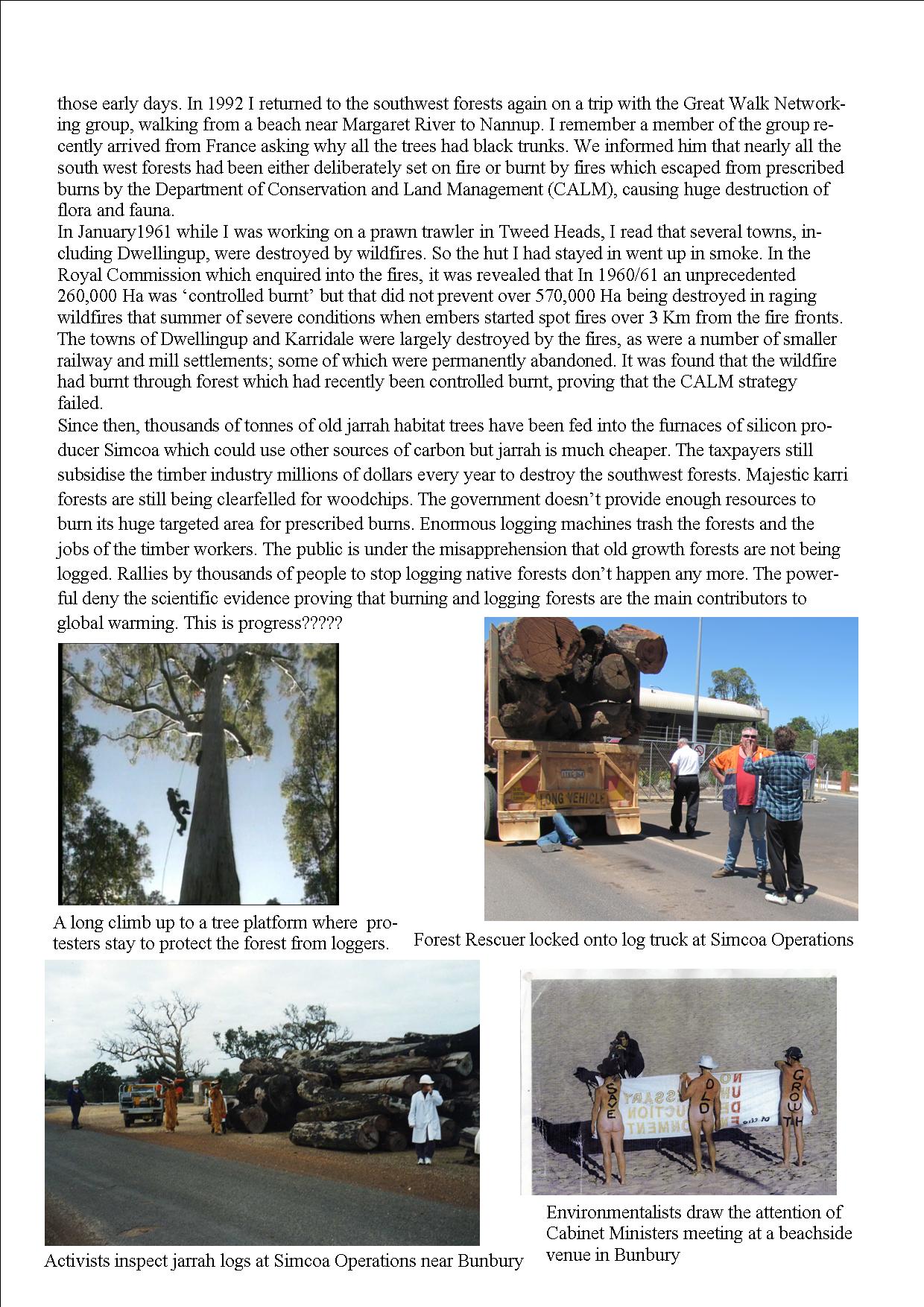

Lost Mail

Best Bloke in Kalgoorlie

BEST BLOKE IN KALGOORLIE

Prologue It was grade hockey grand final day in Melbourne in 1965 and I was pounding down the left wing in control of the ball and had just eluded the opposition half-back. The full back was out of position and only the goalie was between me and the goal. The score was 2 all and it was late in the final half. Suddenly the half-back’s stick was pushed between my ankles and arse-over I went. A sharp pain speared up my left leg and on looking down, I knew what was wrong because my knee and my foot were pointing in opposite directions, just as they had 2 years earlier in the Antarctic. It was a spiral fracture involving up to seven bones. Unlike the previous occasion, from the twist in my sock I knew which way to turn over to get the bones back into approximate position so I quickly turned over, which conveniently put me over the sideline and off the field. It also made a sickening crunching sound.

The coach came running up calling “Get up, get up and take the free hit.” I declined and told the coach to put on the substitute, which he reluctantly did to good effect because my team, Camberwell, scored another goal and won the premiership. Meanwhile, Faye and her friend who had done nursing training together, came to me and put a supporting improvised splint and bandage on my ankle and brought our car onto the grounds next to me. There was a problem! Faye had let the driving licence she had obtained in Meekatharra lapse because she had no ambition to drive in Melbourne, so she could not drive and we had to get a young player, Dennis, to drive us. Because of my aversion to hospitals I insisted on being taken home to recuperate and avoid the Saturday surge of drunks and violence and overdose survivors. With two hockey sticks for support and some discomfort, I hopped inside to bed where Faye applied a much better supporting figure 8 from elastic bandage. Having my left leg poking up vertically was the most comfortable position but it had to be temporary so I could not get to sleep and nor could Faye because of my grunts and groans. She got up and made me a cup of hot malted milk to relax me. I drank it with appreciation until I noticed a big pill undissolved in the bottom of the cup. Faye blushed because she knew I would refuse consume pharmaceuticals but I understood her wanting to relieve my pain and get some sleep for herself. But I left the pill in the cup.

After a restless night for both of us, I agreed that I needed to go to hospital to have a cast put on the leg and to borrow some crutches and also to get a certificate to explain my absence from work next week. We did not want to pay for an ambulance so we set up a dual driving arrangement. Fortunately the FC Holden we had driven over from Meekatharra had a bench front seat which allowed Faye to sit close with me in the driving position so that she could operate the clutch with her right foot while I operated the accelerator and brake with my right foot. Traffic was comparatively quiet about 9 o’clock on this Sunday morning and we successfully drove to Box Hill Hospital to sit in the waiting room with the only other occupant; a young bloke with an obviously broken wrist. He told us he had sustained the injury in a fight and had been waiting since 8 am. Faye and I read our way through most of the ancient magazines on the bench until at last I was called in at about 2 pm with the guy with the broken wrist still waiting. An X ray confirmed that a spiral fracture had broken the same 7 bones as 2 years earlier, but in different places. A cast was plastered on up to my knee and I was given a pair of crutches, a certificate to send to my employer and a packet of pain-killers which I handed to the guy with the broken wrist who was still waiting as we left. Faye had waited all this time for me and again worked the clutch on the way home but told me she didn’t want to do that any more.

When I had nearly run out of the heap of money waiting when I returned from the Antarctic where I had been employed by the Bureau of Meteorology, I contacted the Bureau and was given a job as a relieving weather observer at Kalgoorlie. Then I was permanently employed as a weather observer on 7 day 8 hour shifts at Meekatharra where I installed my bride after a commuting courtship for three days every three weeks between Meekatharra and Perth in the FC Holden. In 1965 my application for a promotion to Technical Officer in the Instruments Section at the head office in Melbourne was successful and anything to do with hydrogen landed on my desk. There were about 70 weather stations in Australia and its offshore islands and the Antarctic and they all used hydrogen in the balloons that were released every day. A few metropolitan observer stations used commercially obtained hydrogen but the vast majority generated hydrogen in a high pressure cylinder using a chemical reaction between ferro-silicon and caustic soda. Part of my job was to investigate accidents that inevitably occurred with corrosive chemicals and highly flammable hydrogen which became highly explosive when mixed with air. Also there had never been a comprehensive manual written on how to safely generate the hydrogen and inflate balloons and that was my main job but it was constantly interrupted by visits to factories which manufactured the generating equipment and trips to the Maribyrnong rocket testing ground where I had great fun replicating and photographing explosions and fires. Part of the conditions of employment was that I would use my own vehicle to travel to the various locations necessary for carrying out my duties in return for a generous mileage allowance. Travelling the 12 km to work in the city during peak hours was the part of the deal which frustrated me the most because I could rarely go fast enough to get into top gear and I am not renowned for my patience. My boss would not believe me when I gave that as the reason for resigning the next year but I just could not hack Melbourne traffic.

On Monday morning I rang the boss of the Instruments Section and told him I would not be able to drive to work for a while. He was very concerned; not for me but because an accident report had just come in and needed my immediate attention. The hydrogen generating cylinders were on pivots so that they could be emptied of residues and washed out between operations. The valve assembly on the shoulder of the cylinder incorporated a bursting disc designed to allow a rapid release of pressure if it went above 2300 pounds per square inch (psi). If the valve assembly was not correctly aligned, when the disc burst it would discharge hydrogen in a jet which started spinning the cylinder like a Catherine wheel and on one occasion the heavy cylinder had shot through the roof of the generating shed. To prevent this, I had designed a bent copper tube which directed the jet down along the cylinder so that there was very little force to turn the cylinder and that had worked in our trials. This latest report stated that the gas jetting from the tube had, for some unknown reason (no Googling in those days), ignited into a very hot flame and I had to sort out this dangerous situation. I told the boss the train station and the tram stop was too far away for me to go on crutches and Faye did not have a driving licence and I could not drive safely with a cast on. He said he would ring back and in an hour he did. A Commonwealth car would pick me up at 8.30 next morning and collect me at work at 4.30 pm and this would continue for 3 weeks. Other staff of the Instruments Section would drive me to where I had to go during the days. All my recuperating had to be done today. I did not complain because Faye would be away at work (travelling by tram for a change) during the day and I would be restricted in what I could do by having to cart the cast around. Next morning the shiny black Commonwealth car arrived in our driveway and all the curtains up the street were tweaked as the residents wondered who that bloke down at number 2/12 really was.

Yarn Some of the Instruments Section staff, including me, were in the habit of having a counter-lunch on Fridays at the pub a block down the hill in Victoria Road. By the time I had stumped down the hill the next Friday the others had ordered my lunch and bought me a beer and we settled in our usual corner only to be interrupted by a loud-mouth who had obviously been in the pub for some time. He loudly asked me if I had broken my leg playing footy. I answered “No, hopscotch.” He looked a bit belligerent and asked me which footy team I barracked for. “Railways” I answered. “Where the hell do they play?’ he leered. “Kalgoorlie” I replied. His face lightened as he asked me if I had been to Kalgoorlie and brightened when I answered that I was born there and had played for Railways Colts. “Then you would know Bill Symons, the best bloke in Kalgoorlie”. “Yes, I know Bill Symons but he is the second best bloke in Kalgoorlie”, I countered. The belligerent expression returned as he demanded to know who I thought the best bloke in Kalgoorlie was. “Jack Vukovich” I asserted. His face changed again as he deliberated. “Yeah, you might be right but why do you pick him?” “I am biased because he is my father” I answered. He grabbed and shook my hand and quickly brought me another beer and dragged me over to a stool near the window where we could have a conversation away from the crowd. We talked about how Bill was the easiest touch in town and would feed every deadbeat who approached him and lend them money he rarely got back. He had bought a pub in Hannan Street with $20,000 he had won gambling and famously named the pub ‘The Twenty Grand’. He didn’t make much profit but enough to run the pub for many years and have an enjoyable life doing it. And we talked about Jack the taxi driver who many prospectors trusted and relied on. They would hire him to drive them out to their digging perhaps 50 miles out of town which was a location they wanted kept secret and arrange for him to pick them up some weeks later. If he didn’t, they could be in big trouble because they had no communication with the outside world, but he always did, which showed what a competent bush navigator he was. If they struck a good patch of gold they would cash it and give the money to Jack and he would give them enough every day to have a good time but not enough to blow a big hole in their pile at the two-up or the SP bookies. When they only had enough left for the next stretch at the diggings, he would help them buy supplies and drive them out again. If they hit poor dirt, he would stake them to a week in town and supplies for the next prospecting trip.

While we were waffling on, my colleagues went back to work, asking if I was coming but I chose to stay and consume more beer and yarns. After a while we were interrupted by the uniformed driver of the Commonwealth car in a bit of a lather telling me he was causing a traffic jam by being double-parked on Victoria Road in peak hour and would I please hurry out to the car. This I did and I heard that this incident was one of the main topics of conversation at the pub for the week with the patrons wondering why that scruffy bloke would be chauffeured in a Commonwealth car.

Epilogue While inspecting some equipment at a factory the next week I told the foreman about the problem with the igniting hydrogen. Without a word he took me up the aisle to a steam valve which he opened fully. Above the resulting roar he shouted ‘look in there” and pointed at the steam jet. Soon I noticed what he was indicating; sparks appearing intermittently at the end of the outlet. I nodded and he turned the valve off. “That steam is only 200 psi pressure so there would probably be more sparks at over 2000 psi” he said. I included his revelation in a report and suggested that the valve arrangement be left unaltered and the operators warned about the intense heat of the flame and the advisability of charging the cylinder with the correct dose of chemicals so that the bursting disc remained intact. This suggestion was accepted. In 1966, when I had completed the hydrogen manual, I resigned and Faye and I boarded a ship bound for New Zealand with our FC Holden as deck cargo. New Zealand was leading the world in the development of ferrocement yachts and I was interested in the advantages of that hull material and wanted to see what was going on so that I could build one if they lived up to my expectations.

|

|

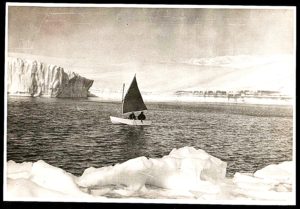

Antarctic Sailing

Antarctic Sailing

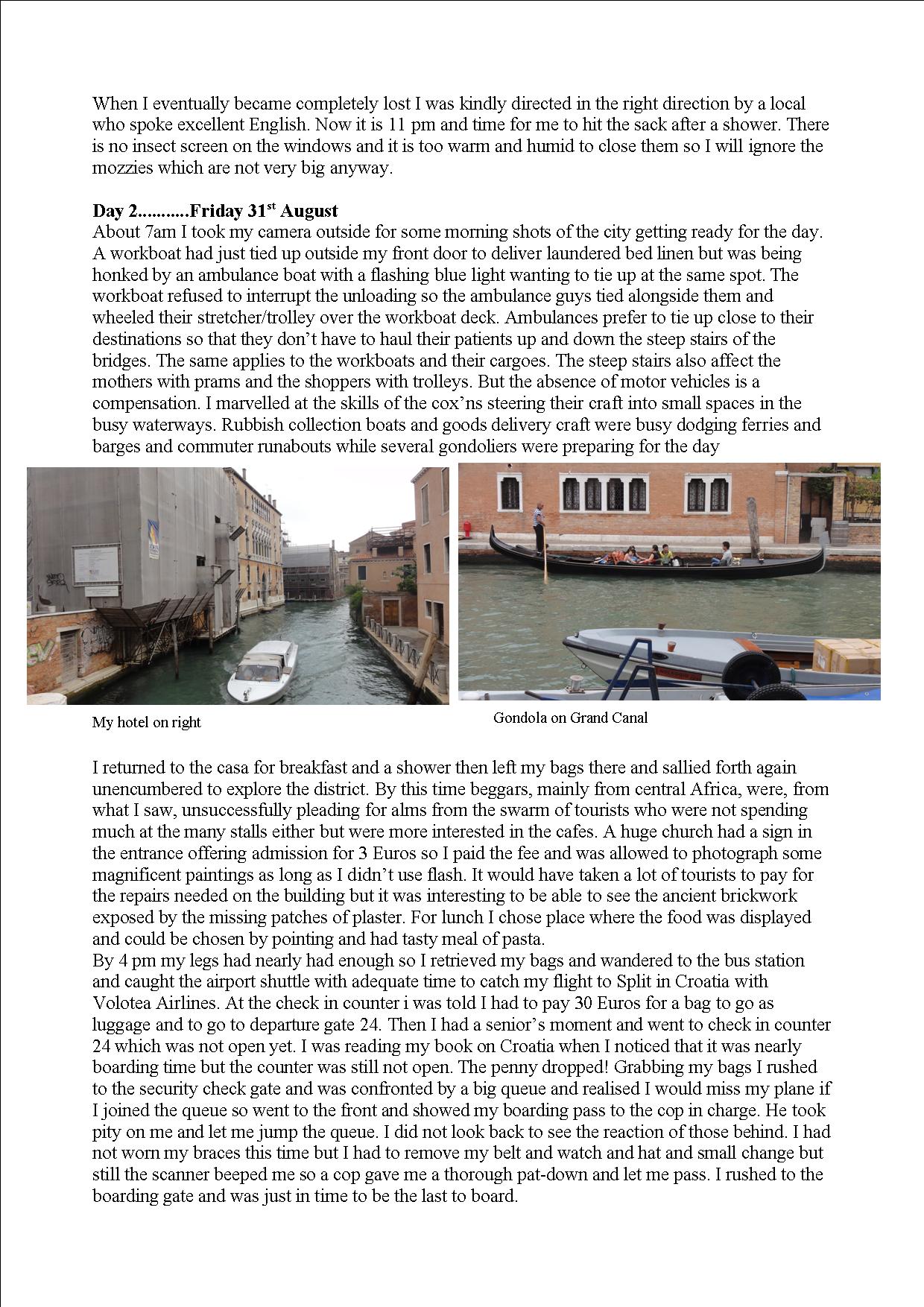

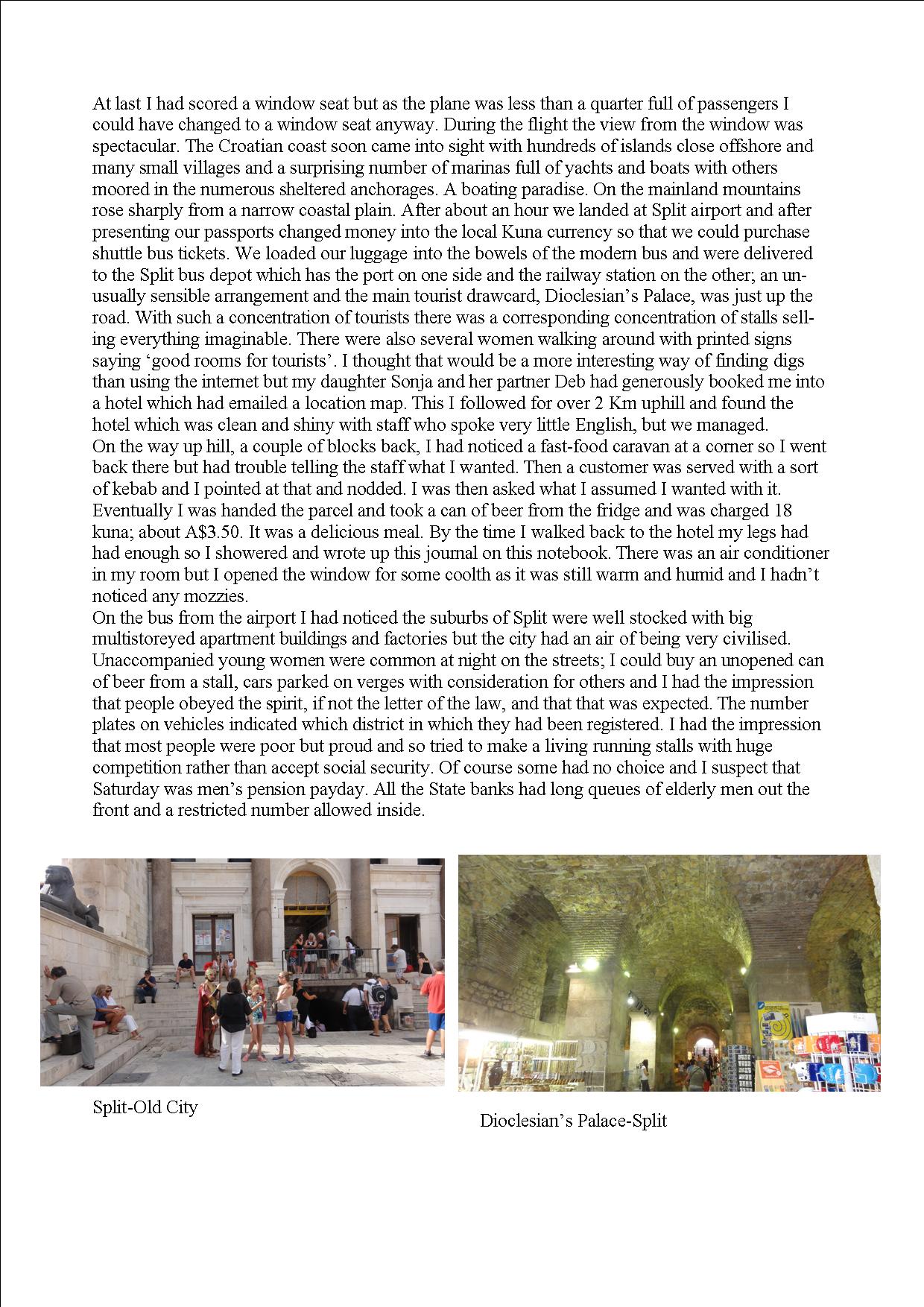

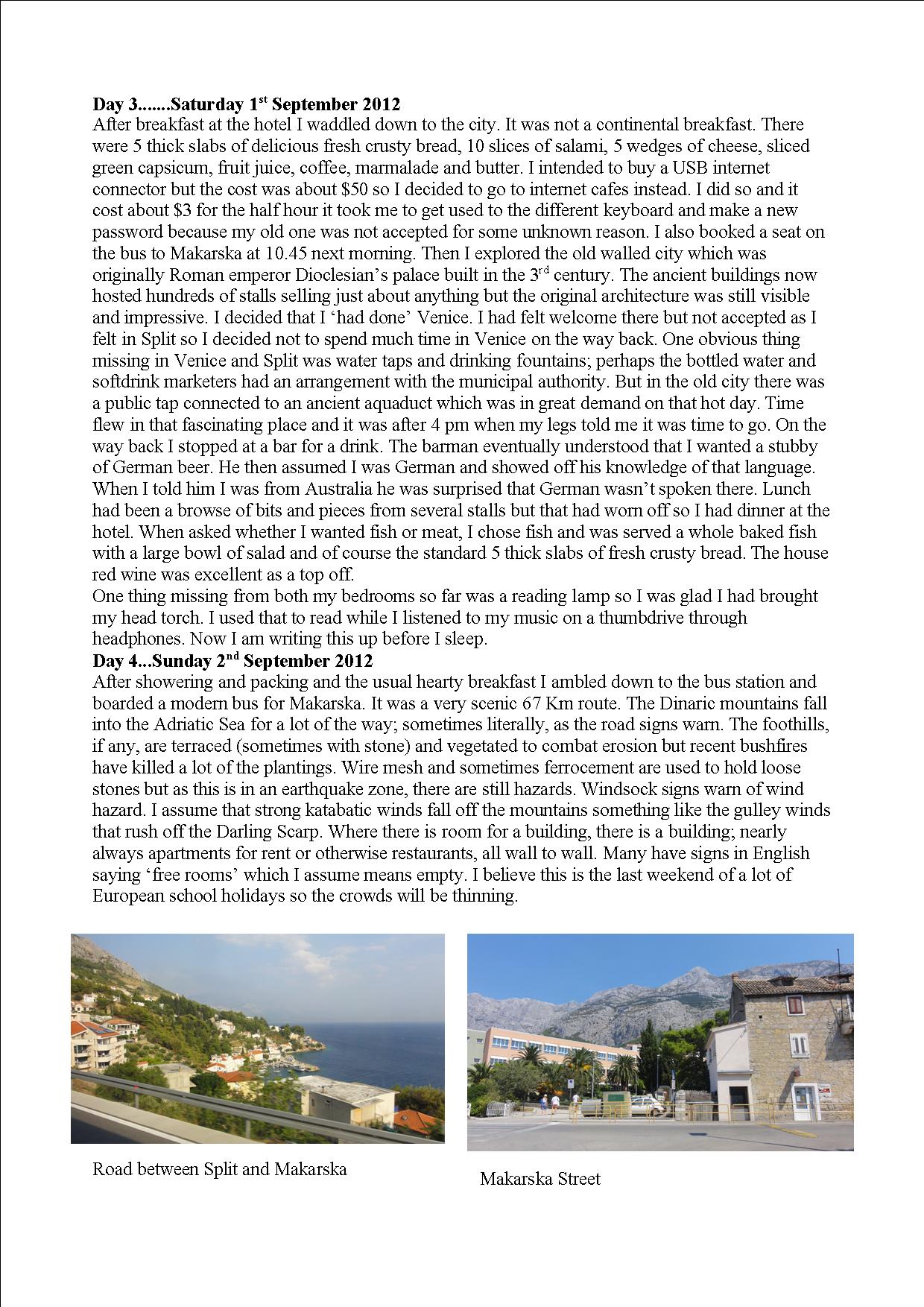

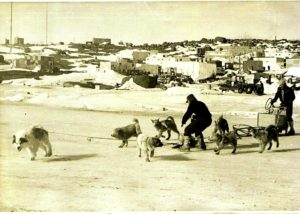

At the Mawson Antarctic Base in 1963 there was a10 foot aluminium dinghy which was used for rowing out to small close-offshore islands for the maintenance of radio aerial towers. Most of the year the islands could be accessed on foot over the sea-ice but for about 2 or 3 months Mawson looked like a seaside village.

In previous years I had ocean raced and cruised in various yachts and had a yen to sail in the spectacular Mawson Bay, dotted with ice floes sometimes occupied by penguins and seals and ringed by ice cliffs which occasionally broke off with a tremendous crash and splash to form icebergs. So I set about making the dinghy sailable in what little spare time I had available.

Besides the employment for which we were paid, everyone had extra jobs as well as nightshift duty every 3 weeks and training to take over scientific jobs to relieve scientists’ routines when they were away on field trips. Nightshift was a constant patrol of the whole base, checking that the heaters were fuelled and setting up the ‘flaming fury’ lavatories but mainly watching out for accidental fire which was the most feared hazard in the Antarctic. I was employed as a weather observer on shift work and my main subsidiary job was to be responsible for the husky pack and to train the pups when they were born mid-year but until then I could squeeze in a few hours to devote to converting the dinghy into a sailing craft.

I was given access to the well-equipped carpentry workshop and the mechanics were generous enough to use their genius to make fittings for me out of scraps. They made fittings for a rudder to be swung on the stern and a gooseneck to fit to the mast for swivelling the boom. I found ropes and blocks for the running rigging and a damaged tent for the mainsail. There was plenty of wire rope for the standing rigging to which I spliced eyes for fixing to the gunwhales. There was not a pole long enough for a Bermuda-rig mast so it had to be a gaff rig. A centreboard was too challenging to fit so lee boards were substituted. I made these and the mast and gaff, rudder and tiller in the carpenter’s workshop.

The base OIC (Gaffer) was a yachty and reluctantly gave me permission to go ahead with the project when he heard about it. He was worried about the ramifications of a capsize in the freezing waters. The crew would be wearing layers of warm clothing which would make swimming ashore unlikely within the 3 minutes before lethal hypothermia set in. Then there was the katabatic winds that made a capsize somewhere between possible and probable. The katabatic wind is caused by dense cold air from the Antarctic plateau at an altitude of about 1500 metres rolling downhill on the steep slope to the sea. These winds can occur with little warning and turn into 150 km/hr blizzards within an hour. If we were blown out to sea the closest rescue vessel was thousands of miles away.

There was urgency to set sail before the bay froze over and at last we were ready to launch as the days became much shorter. Besides the Gaffer, there was no-one on the station with sailing experience but several novices were keen volunteers for their first sail. The Gaffer was not one of them and Alan won the toss

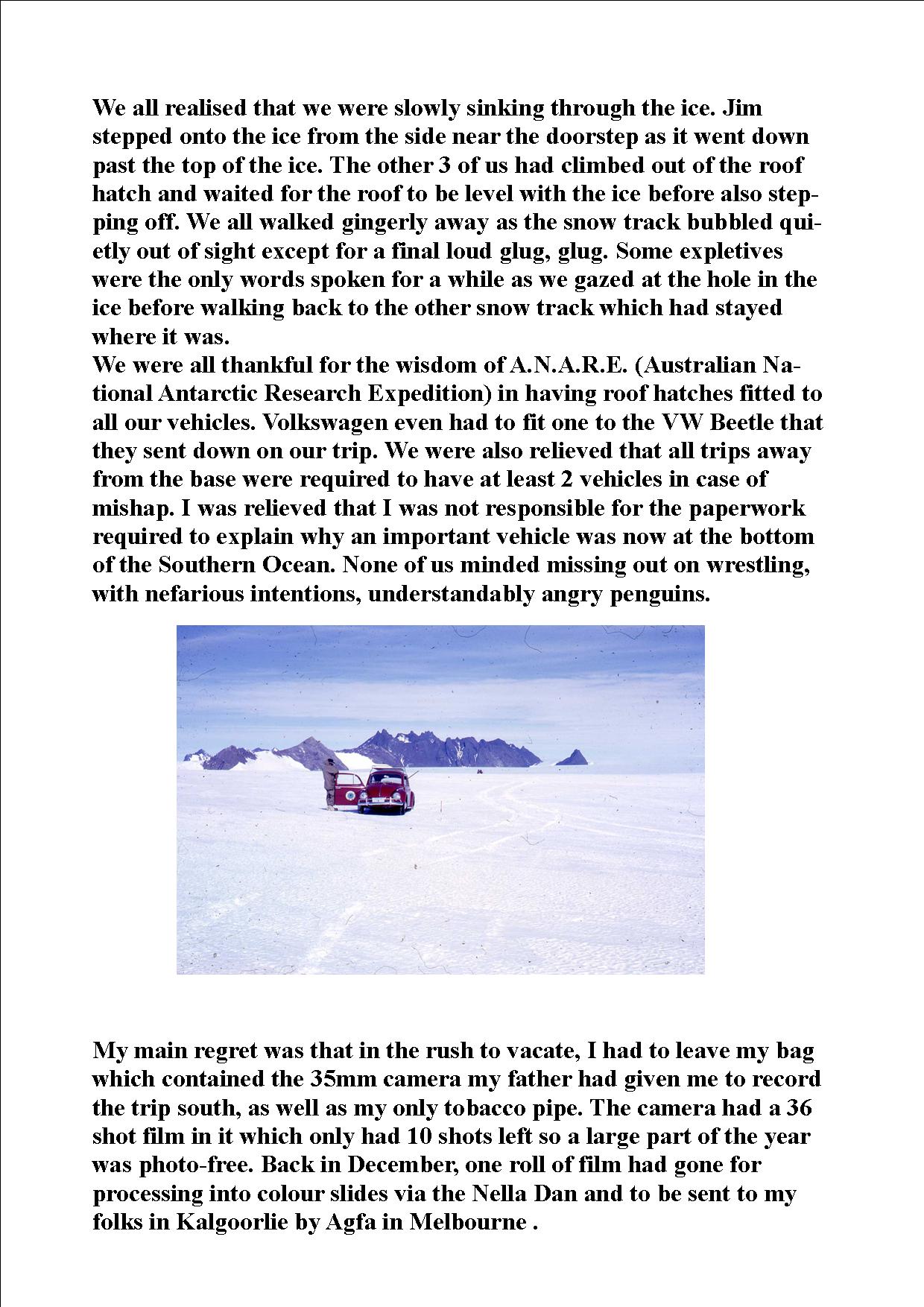

Launching day was sunny and relatively warm at minus 2 degrees C as Alan and I climbed aboard with most of the base crew watching. The wind was light and just enough for us to sail around the spectacular bay getting close to the towering ice cliffs and then around the radio masts on the islands. After about half an hour the wind freshened and Alan had to hang out over the side to keep us upright but that became more difficult as the wind became stronger so I tacked towards shore with wave tops splashing on board.

As we nudged the rocky shore there was a deep puddle in the bottom of the dinghy and we were quite damp but still exhilarated as the spectators gave us a cheer. The wind continued to strengthen, causing a big chill factor so we hurriedly de-rigged and turned the dinghy over and secured it to steel pegs fixed into the rock before going to our donga to dry and warm in front of the briquette-fuelled heater before heading to the mess for lunch.

Next day the Gaffer told me that our dinghy had been the first yacht in Antarctica because the word ‘yacht’ was Dutch and translated as ‘a sailing vessel used for pleasure’. He was sure no other vessel fitting that description had sailed in Antarctica before. I asked him what he meant by ‘had been’. He answered that the dinghy had blown away during the night. Now I know how to secure a dinghy to withstand a cyclone so I knew that if it had blown away someone had helped that happen and I suspected that it had been the Gaffer but I did not comment. He was responsible for the safety of everyone on the base and sailing down there definitely was hazardous.

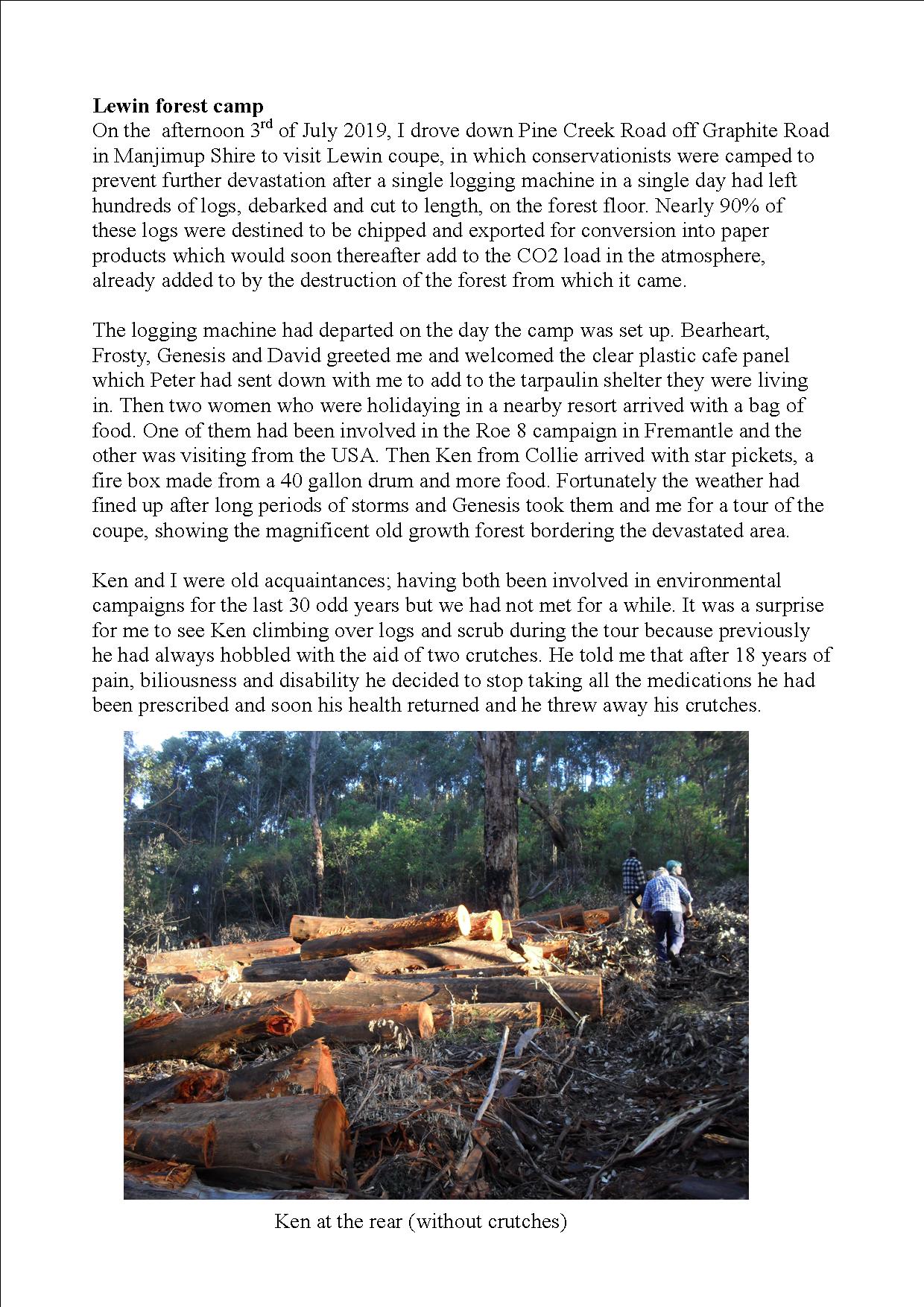

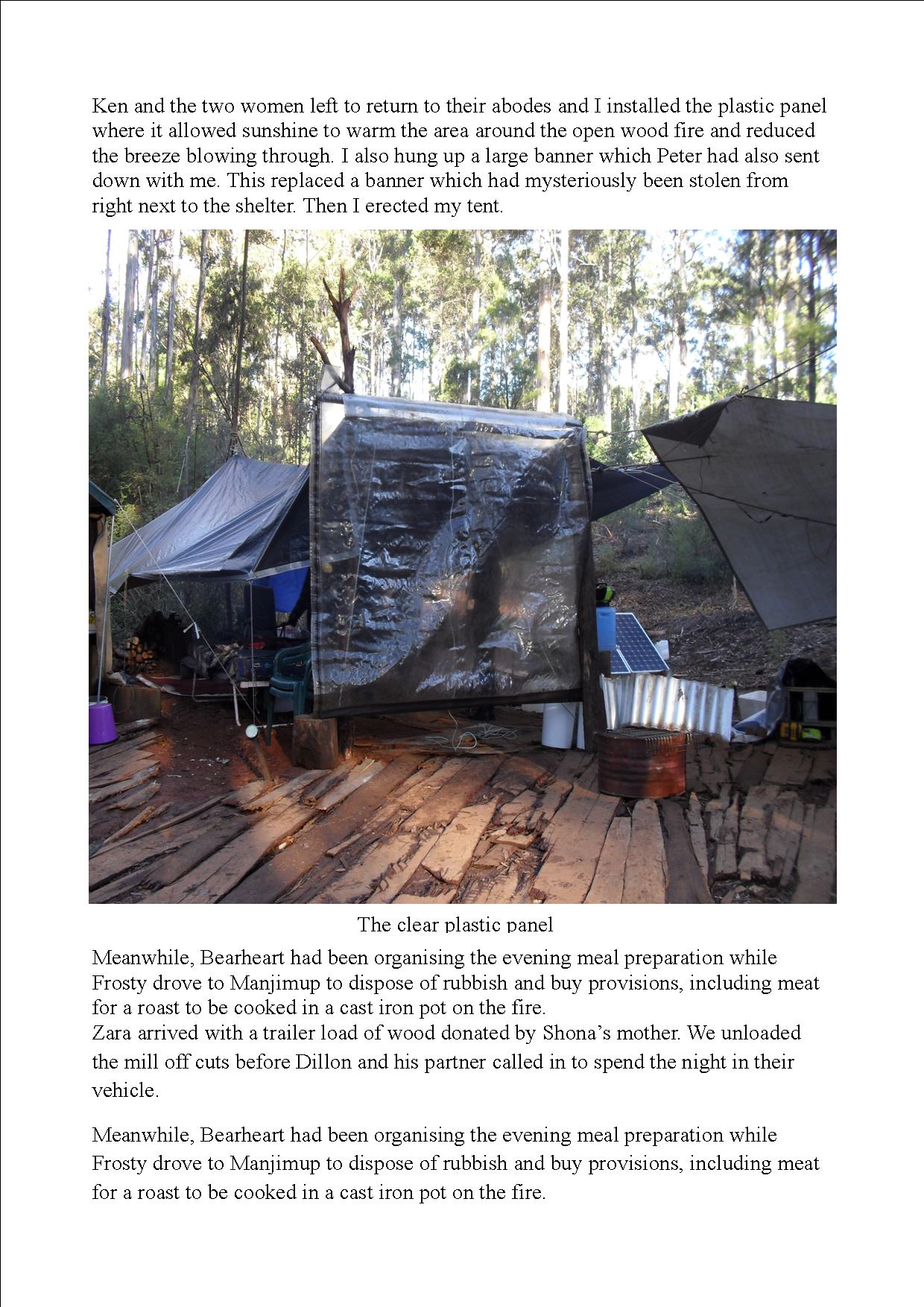

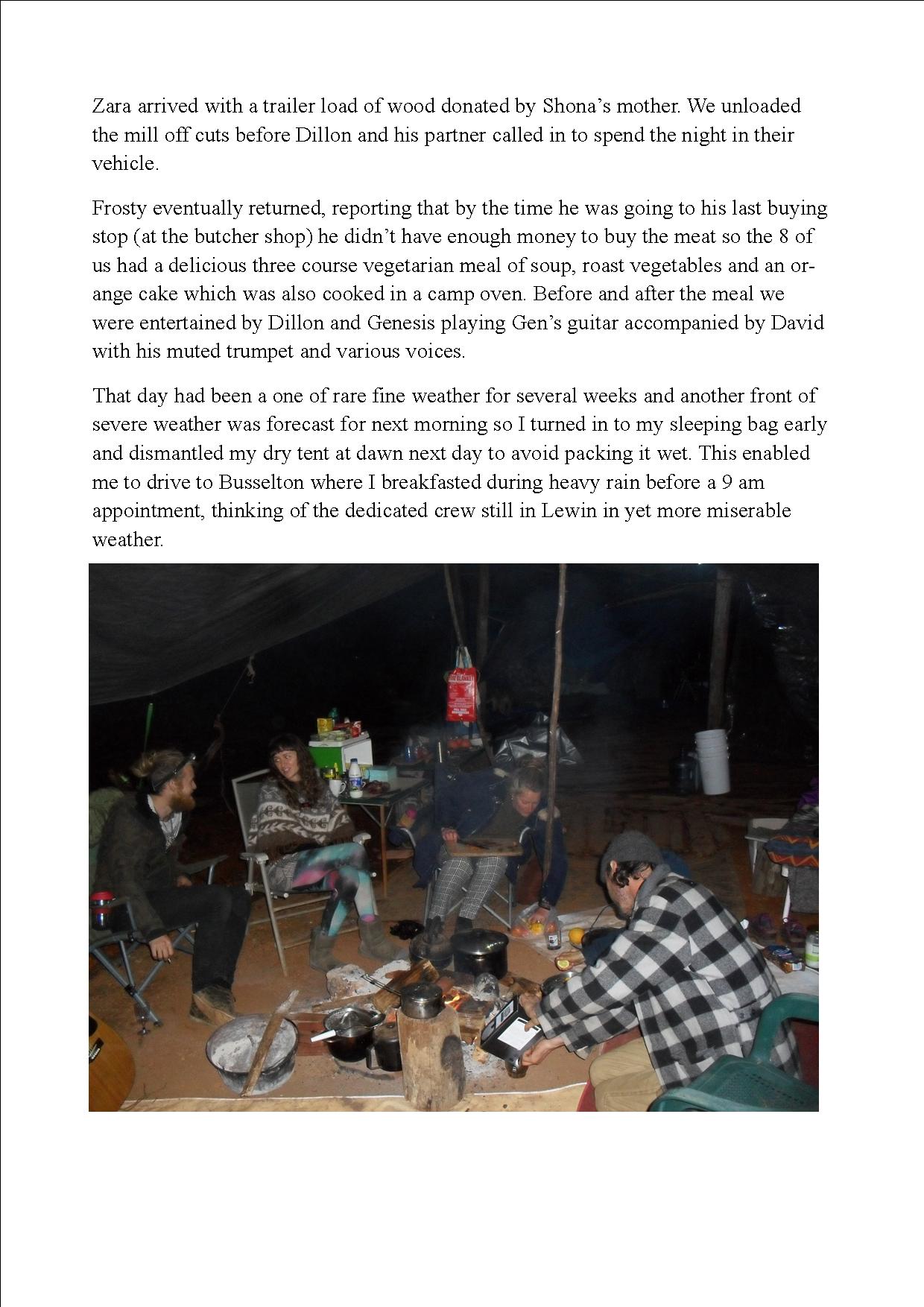

Lewin-camp-visit